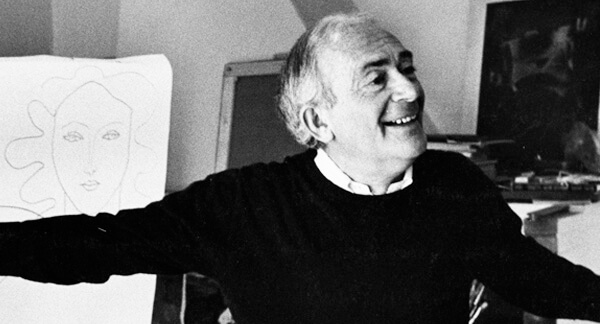

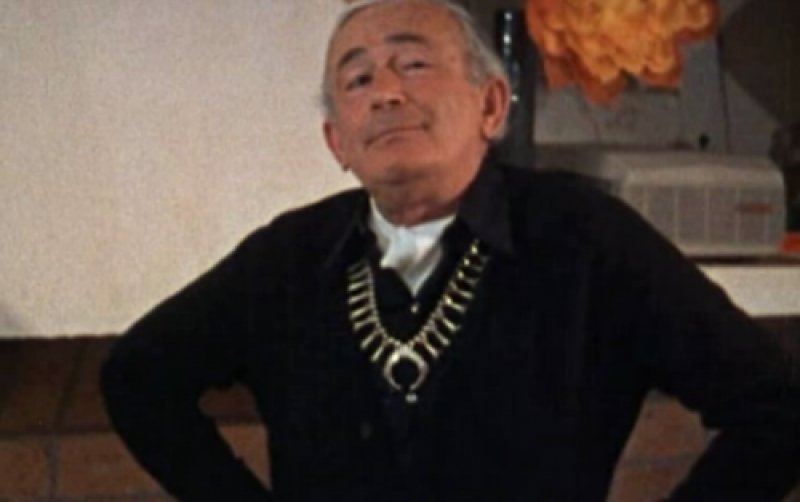

Elmyr de Hory is considered by many to be the most talented and successful art forger in the world. Striving for a career as an artist, with some misfortune, he realized along the way that he had an exceptional gift for imitating the styles of the great modernist masters. However, these forgeries, which passed unnoticed for decades by many art experts, were just one more branch of a mysterious existence steeped in deception.

Early life.

After contrasting the information with research and testimonies, today it is known that Elmyr was born in 1906, as Elemér Hoffmann in Budapest, Hungary. He began his formal art training at theNagybánya Artist’s Colonyat the age of 16, and continued at the Akademie Heinmann art school in Munich. In 1926 he moved to Paris and enrolled at the Académie la Grande Chaumière, where he studied with Fernand Léger.

As for his family, Elmyr always said that his father was a Catholic christian and a diplomat, belonging to the aristocracy; but the Budapest registry list him as a Jewish handicraft merchant. He also said that the Nazis murdered his family, but according to the testimony of Mark Forgy, his personal assistant-apprentice for more than a decade in Ibiza, Elmyr was visited several times by an alleged cousin of his, who in the end turned out to be his brother. The fact that he was persecuted by Nazism, being Jewish and homosexual, was possibly the catalyst for creating false identities, and perhaps finds its origin in the need to take care of his image and obscure his trail to save his life. In any case, what is supposed to be known about his identity may still be open to another “plot twist” in the future.

Elmyr De Hory tended to create his alter ego of an aristocratic origin, who had been through recent episodes of misfortune and felt compelled to sell his possessions to finance his high standard of living. According to Elmyr, the portrait he owned of him and his brother was made by the famous Hungarian portraitist Philip de László. However, when in 2010 Mark Forgy, as the sole heir to all of Elmyr’s paintings, exhibited this same portrait the De László Trust declared that the work was certainly not painted by the esteemed portraitist, but simply another of Elmyr’s forgeries. The fact that De Hory forged a double childhood portrait of himself and his brother in sailor suits (a brother who, according to him, was no longer alive …), signed on behalf of an artist who at that time only portrayed the elite of the European plutocracy, seemed be a link to validate all the lies about his origin.

By the time the young Elemér finished his art studies in 1928, his style of figurative painting became obsolete as new avant-garde trends emerged such as Fauvism, Expressionism and Cubism. This harsh reality and the economic shockwaves of the Great Depression clouded any prospect that he could make a living from his art.

Police files in Geneva, Switzerland, indicate misdemeanor charges and arrests between the late 1920s and the 1930s. During this period, he was convicted ten times in five European cities for crimes including check fraud, document forgery and false claim to an aristocratic title. This indicates that his skill at artifice had its origin in financial fraud, probably driven by an inability to live within his lifestyle of high means.

At the outbreak of World War II, de Hory returned to Hungary. He soon ended up in a Transylvanian prison in the Carpathians for political dissidents; due to having been involved with a British journalist and suspected spy. Although he was later released during the war, only a year later, it is assumed that he ended up in a German concentration camp for being Jewish and homosexual. However, this story has never been confirmed. Edith Tenner, the widow of Elmyr’s maternal cousin and his only surviving relative, suggested that the forger may have spent the war in Spain. Other close sources say that he escaped from the hospital of a German prison and then later emigrated to Hungary.

The bon vivant forger.

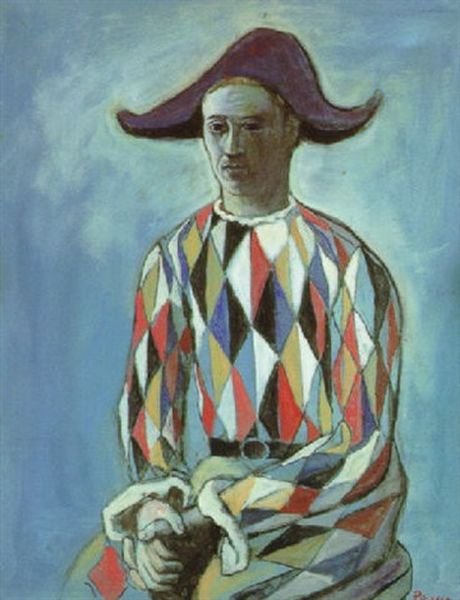

Arriving in Paris after the war, once again De Hory had initially little success in making a living from his art. Instead, he realized his astonishing talent for copying styles from prominent painters. His career is supposed to have started when he managed to sell a pen and ink drawing to a British woman as an original Picasso. Having lived through repeated unsuccessful attempts to ignite his own career, Elmyr focused on his talent for imitation, selling his replicas to renowned galleries in Paris pretending to be the displaced Hungarian aristocrat selling his family’s art collection.

For a time, he focused on counterfeiting works on paper, as the correct paper was easier to obtain and these works could go unnoticed more easily since many of the artists he forged, such as Picasso and Matisse, were still alive and they could realize a new painting on canvas. This “flying under the radar” technique of doing only minor works even led him to produce fake lithographs.

De Hory avoided using any type of pigment on paper until 1949, when he began adding gouache and watercolor to his ink drawings; solving the added complication of color with bulb-assisted drying and aging the paper with some tea brushing.

When producing works on canvas, Elmyr used to buy 19th century works at flea markets and scrape them, aware of how forensic examinations of the mediums were produced. To artificially age the works, he used two widely available commercial varnishes: Vernis à craqueleur, a varnish that produced rapid cracking, and Vernis à vieillir, which imparts a tinge of golden aging.

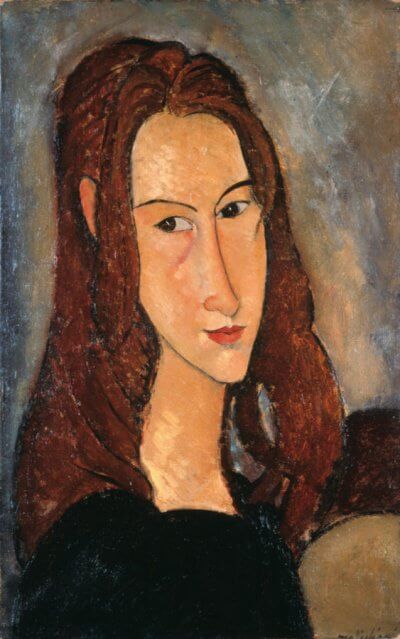

In 1947 Elmyr moved to New York. Later that year, he was able to find a correct stretcher on a vintage canvas, tested his first Modigliani painting, and baked it in the oven to dry the oil paint. Even so, the oil took two months to dry, but the resulting one was easily sold to the Niveau Gallery in New York. Soon after, he would expand his repertoire of forgeries to include works by Matisse and Renoir as well, but throughout his career he concentrated largely on Modigliani – since he was an artist with a very short life, his works rare and object of desire by many. From that point, Elmyr began to create an illusory world around himself that gave his art and himself the appearance of authenticity. This brought him friends, clients, and acceptance. To avoid suspicion, he had started signing the works under many pseudonyms: Joseph Dory, Joseph Dory-Boutin, Louis Cassou, Elmyr Herzog, Elmyr Hoffman, and E. Raynal are some of them.

In 1960, De Hory struck a trade deal with two art dealers, Fernand Legros and Real Lessard, who devised many of the most brilliant and insidious tactics to corrupt the epistemological mechanisms that govern the art market.

Above all, Legros and Lessard recognized the importance of hiring art experts who could “guarantee” the authenticity of works. They knew who to bribe and who to cheat. At some point, they even managed to convince the artist Kees van Dongen that he himself had painted a work by Elmyr De Hory. By holding an exhibition on Raoul Dufy, they made sure to mix authentic works with those made by Elmyr. They put forgeries up for auction and then bought them back, giving the paintings the authority of having previously been publicly sold. To ensure a supply of reliable precedents they had stamps copied and produced their own documents. They did the same with the customs stamps, which facilitated transport and in turn provided an artificial provenance. They bought prewar monographs because the plates were easy to replace with a photographic copy of a De Hory forgery.

Few events in the art world confer as much status as the inclusion of an painting in a book, as it signals an almost unquestionable authenticity and elite status. Both the dealership duo and Elmyr understood how to exploit the weak points in the system. During the 1950s and 1960s, De Hory is believed to have forged more than a thousand works by great artists that were sold across five continents. Many have been removed from museums. Others, some experts say, have not been and perhaps never will be. De Hory created so many forgeries of Amedeo Modigliani that it has become impossible to compile a definitive catalog of the artist’s original work, according to Kenneth Wayne, director of The Modigliani Project.

However, no new forensic techniques for analyzing pigments were anticipated by Elmyr nor the dealers. Most likely, this was due to a lack of knowledge about the history of the paintings, as it relates to their composition, and therefore the inability to anticipate that new forensic techniques such as X-ray fluorescence and Raman spectrometry would unveil their scam. These technologies can quickly determine elemental and molecular compositions and identify materials that shed light on a production date which was later than the painting claims to be, and in this last and crucial respect, De Hory’s artifice could be exposed.

In 1964, many experts and art galleries became suspicious of these works, when Legros sold 56 fakes to Texas oil millionaire Algur Meadows, who discovered the fraud and alerted Interpol, exposing De Hory as the artist behind the works. . The police were soon on the trail of Legros and Lessard. Legros sent De Hory to Australia for a year to keep him out of the eye of the investigation.

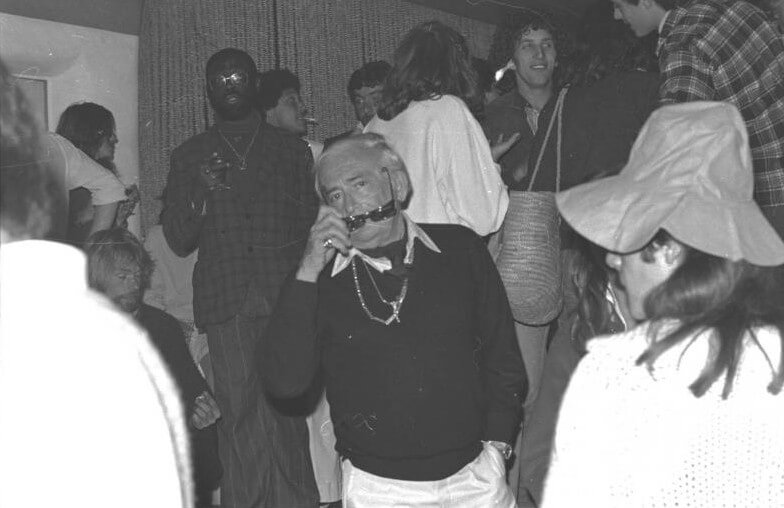

Life in Ibiza.

Most of the works he painted would be done in Ibiza in the 1960s, where he had a hidden studio his villa, named La Falaise. His life was relatively quiet, until the plot was uncovered. Fleeing justice, he soon had Legros co-inhabiting the villa, who claimed ownership and threatened to evict De Hory from La Falaise. Living with Legros was increasingly difficult, so De Hory decided to leave Ibiza. Legros and Lessard were arrested shortly thereafter and jailed on charges of various check frauds.

Tired of eluding Interpol for some time, Elmyr decided to return to Ibiza and accept his fate. It was not until August 1968 that a court convicted him, and solely for crimes of homosexuality, without being able to show any visible supporting evidence and be able to associate him with the Legros and Lessard frauds; sentencing him to only two months in prison and one year of expulsion from the island. During that period he resided in Torremolinos, Malaga.

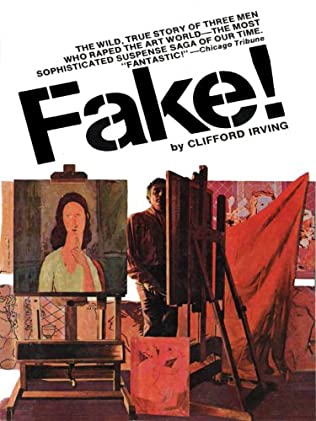

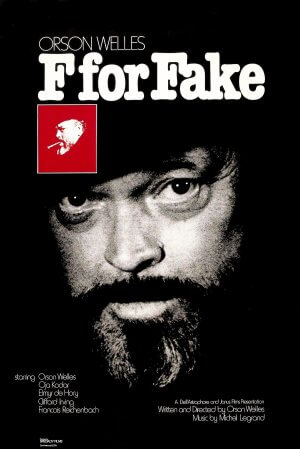

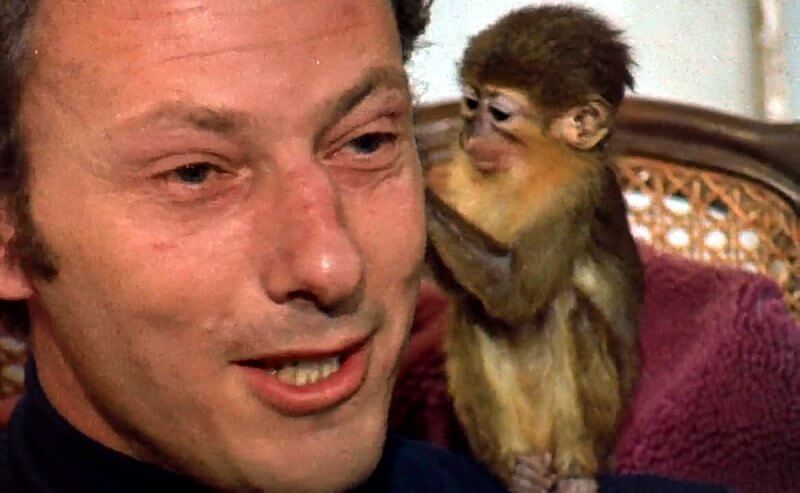

A year after his release, Elmyr De Hory, who by then was a celebrity, returned to Ibiza. Soon after, she told his story to the writer Clifford Irving, who wrote his biography with the title: Fake! The story of Elmyr de Hory, the greatest art forger of our time, who he turned into an international bestseller. Irving himself was later convicted of another fraudulent biography of Howard Hughes, the famous aviator mogul. Shortly before, Irving and De Hory participated in Orson Welles’ documentary F for Fake (1973), which closely portrays this duo of counterfeiters and their abstract circumstances. In the documentary, De Hory questioned that his forgeries were inferior to the original paintings, mainly because they had gone unnoticed by the “reputed” expert class and were appreciated when believed to be genuine. In F for Fake, Welles also raises questions about the intrinsic nature of the creative process and how deception, illusion, or outright fraud can often prevail in the art world; in some respects, minimizing the guilt of the art forger and the outliers around him.

In 1969 a series of recent scandals had connected Elmyr De Hory to forgeries in the United States and France. However, in Spain he was still safe from the consequences. So he embraced his new personality: the great forger who had deceived the art world.

In the early 1970s, de Elmyr decided to try his hand at painting again, but this time he would sell his own original work. Although he had gained some fame in the art world, he made little profit and soon learned that the French authorities were trying to extradite him to stand trial on fraud charges. By rule this took a long time, as Spain was going through its last years of the dictatorship and did not have any extradition treaties with France yet.

On December 11, 1976, Mark Forgy, Elmyr’s assistant and partner, informed him that the Spanish and French governments had reached an agreement to extradite him. Soon after, de Hory took an overdose of sleeping pills and asked Forgy not to intervene or stop him from taking his own life. However, Forgy later went for help to take De Hory to a local hospital, though along the way he died in Forgy’s arms. Later that year, Clifford Irving had expressed doubts about Elmyr’s suicide, claiming that he may have faked his own death to escape extradition, but Forgy had dismissed this claim.

Throughout his 30-year career, Elmyr de Hory inserted more than 1000 forgeries into the art market, many of these works still residing unexposed in museums and private collections today. Living a life that can be seen as one of the greatest works of conceptual art of the 20th century, which in turn meant a deep critique of the art market. The only thing you can be sure of from this phony master is the uncertainty of the legend that surrounds him and the extent of his charade.

References:

Martinique, E. (2019). Elmyr de Hory – The Story of the Most Famous Forger in Art History. Online Art Blog: Widewalls

Taylor, J. (2014). The Artifice de Elmyr De Hory. Online Blog: Intend to Deceive, Fakes and Forgeries in the Art World

Hillstrom Museum of Art (2020). The Secret World of the Art Forger Elmyr De Hory: His Portraiture on Ibiza. USA: Gustavus Adolphus College

Forgy, M. (2012). The Forger’s Apprentice: Life with the World’s Most Notorious Artist. CreateSpace. Print.

Rød, J. (2010). Fake Fakes in the Forger’sOeuvre. Online Blog: Elmyr de Hory: The Official Website by Mark Forgy

It is possible that the pictures and the content reaches us through different channels and is sometimes difficult to know the author or the original source of the content. Whenever possible we added the author. If you are the author of any content (image, video, photography, text, etc.) and do not appear properly credited, please contact us and we will name you as an author. If you show up in a picture and think it impugns the honor or privacy of someone we can tell us and it will be withdrawn.

Kelosa Blog editors are not responsible for the opinions or comments made by others, these being the sole responsibility of their authors. Although your comment immediately appears in Kelosa Blog we reserve the right to delete (in case of using swear words, insults or disrespect of any kind) and editing (to make it more readable) or undermines the integrity of the site