Ibiza’s reputation as the sun-drenched party capital of the world is rooted in a rich countercultural history. Long before the disco era, this Balearic island was a haven for beatniks and other bohemians in the 1950s and 1960s. The beatniks – members of the Beat Generation and their bohemian followers – found in Ibiza a unique refuge during Franco’s Spain, where artistic freedom, cheap living and the carefree attitude of the locals converged. Their presence, less well known than that of their hippie successors, undoubtedly left a permanent cultural imprint on Ibiza, which went from being an isolated backwater to becoming an “island of freedom” in the popular imagination.

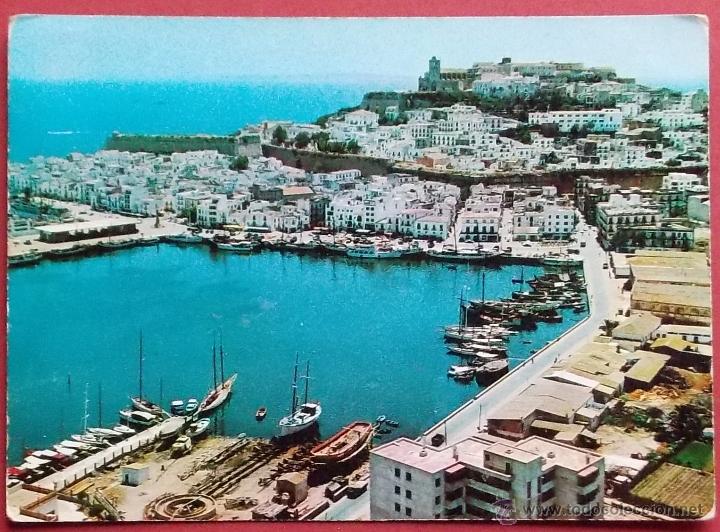

The city and the port of Ibiza: a contemporary postcard as they were in the early 1960s. [Source]

This article explores the historical accounts of the beatniks in Ibiza in the 1950s-60s, the notable figures who visited, the cultural impact they had, and the evidence – documented and anecdotal – of their time on the White Isle.

To situate the reader, since these two concepts are sometimes used interchangeably, it is worth explaining the differences and similarities between beatniks and hippies:

Differences and similarities between beatniks and hippies

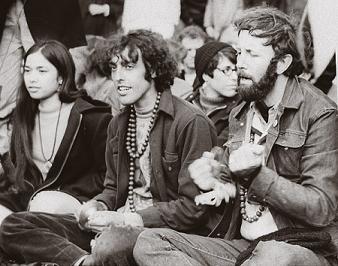

The beatniks, a subculture that emerged in the 1950s, laid the foundations for the countercultural explosion of the 1960s, which eventually developed into the hippie movement. Although both groups shared a rejection of the dominant values of the United States and the West in general, their approaches, aesthetics and philosophy diverged in some fundamental aspects. The beatniks, influenced by writers such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, advocated spontaneity, existential exploration and raw, unfiltered artistic expression. They found inspiration in jazz, Eastern philosophy and a deep skepticism of materialism and conformity. The Beatniks, who preferred a minimalist, bohemian lifestyle, often lived in urban environments and frequented cafes and poetry readings where they dissected the meaning of existence and modern alienation.

By the 1960s, beat values had evolved into the hippie movement, which shared the anti-establishment stance of the beatniks but took a more communitarian, colorful and politically active approach. Whereas the beatniks were intellectuals, with melancholy tendencies, who sought personal enlightenment through literature, travel and solitude, the hippies were vibrant, free-spirited idealists who prioritized love, peace and collective social change. The beats’ love of jazz and smoky cafes gave way to the hippies’ psychedelic rock and outdoor music festivals. Drugs played an important role in both subcultures: beatniks were known for their use of Benzedrine and marijuana, while hippies turned to LSD and other hallucinogens to expand their consciousness.

Ultimately, the hippie movement can be seen as an evolution of the Beat Generation, which took its basic ideas of nonconformism and rebellion and amplified them into a full-fledged cultural revolution. While the Beatniks paved the way with their introspective, avant-garde sensibility, the hippies transformed those ideals into a noisy, colorful and politically charged movement that reshaped the landscape of Western society.

Postwar sanctuary: Ibiza’s bohemian charm

Already in previous decades, Ibiza had served as a sanctuary for outsiders. In the 1930s, the island’s remoteness attracted European intellectual exiles such as German philosopher Walter Benjamin and French writer Albert Camus, who mingled in Ibiza Town’s cafés. After World War II, Ibiza remained largely “forgotten” by General Franco’s regime, which focused on the mainland, making it an attractive escape route despite the dictatorship. In the 1950s, this forgotten quality, combined with the beautiful beaches, mild climate, tolerant atmosphere and cheap cost of living, began to attract artists, writers and vagabonds from all over the world. Everyone seemed to arrive in search of something: inspiration, reinvention, or simply a life of cheap leisure among like-minded souls. As one account points out, “everyone was, or aspired to be, a writer, poet or painter” in 1950s Ibiza.

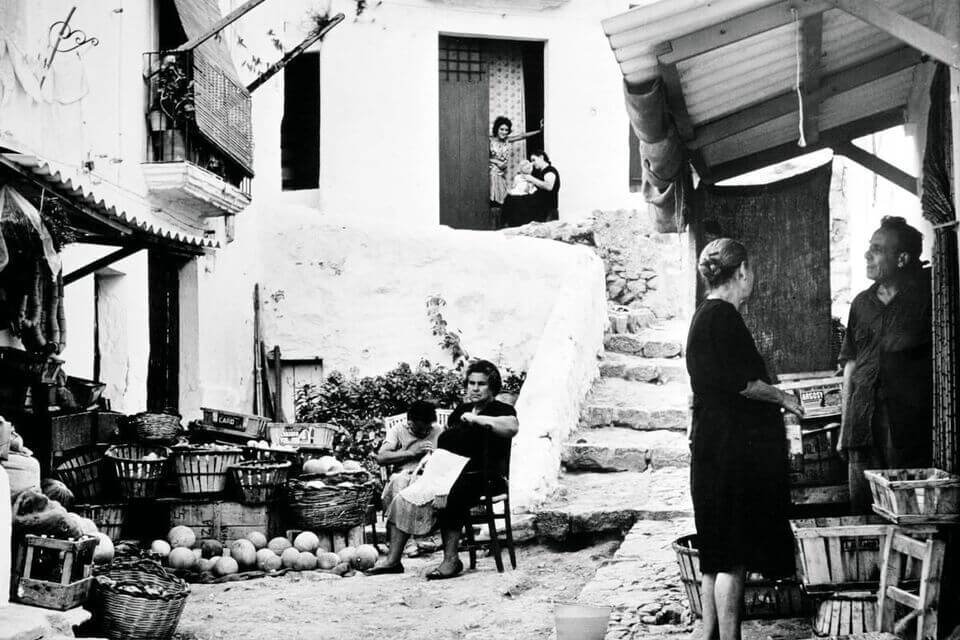

A store in the port of Ibiza (1960s)

In the late 1950s, the stage was set for the Beat Generation to arrive on Ibiza’s shores. Franco’s authoritarian government paid little attention to the goings-on in Ibiza during this period. The island was impoverished and provincial, which strangely allowed a degree of freedom. According to a later resident, Damien Enright, the native population of Ibiza was passive and did not object to foreigners doing as they pleased, nor did the authorities really interfere with the Bohemians. In part, this was because Ibiza was desperate enough economically to tolerate eccentric foreigners spending money. The result was a de facto enclave where alternative lifestyles could flourish under the radar.

Birth of a beatnik haven

The Beat Generation – writers and nonconformists typified by figures such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg – inspired many young Americans and Europeans to travel in search of meaning and adventure. Ibiza’s nascent bohemian scene was already underway by the late 1950s, although the first arrivals did not yet call themselves “beatniks.” A turning point came thanks to a somewhat unusual origin: a jazz club in Barcelona. In the late 1950s, a couple of American mavericks ran the jazz club “The Jamboree” in Barcelona, and when life got too hot (or debts too high) on the mainland, they would escape to Ibiza for a break. “It was they who ‘started’ the Ibiza myth,” recalls Damien Enright, noting that in this small early colony there were ”more Americans than Europeans.” By 1959, a small but vibrant expat community had settled on the island.

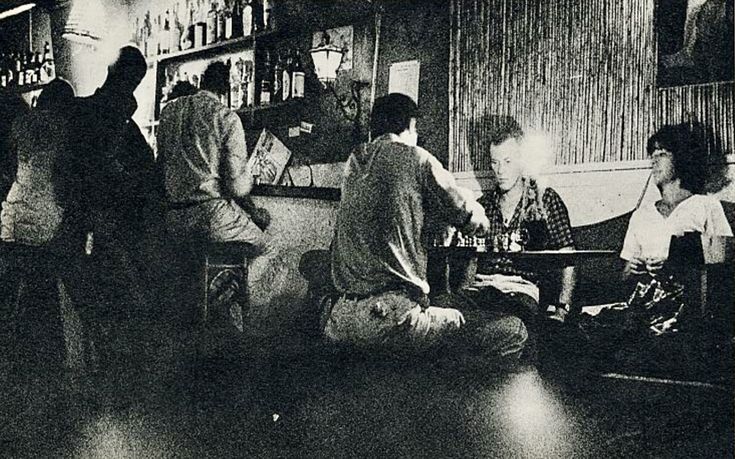

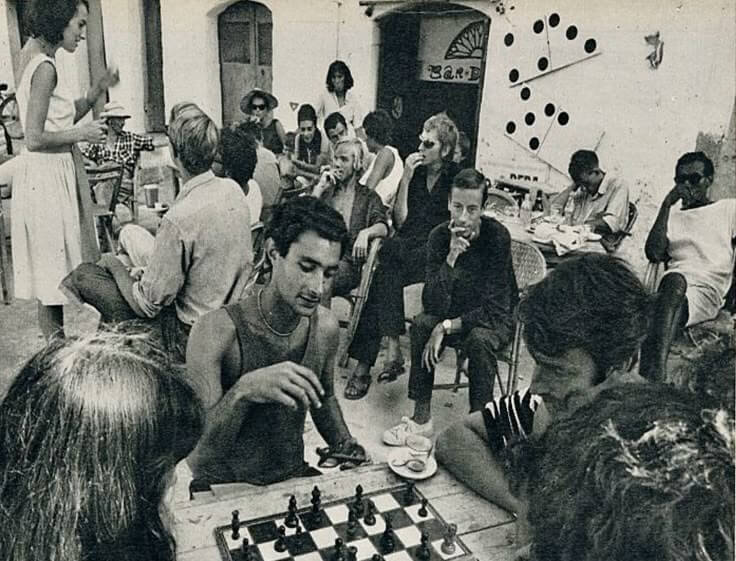

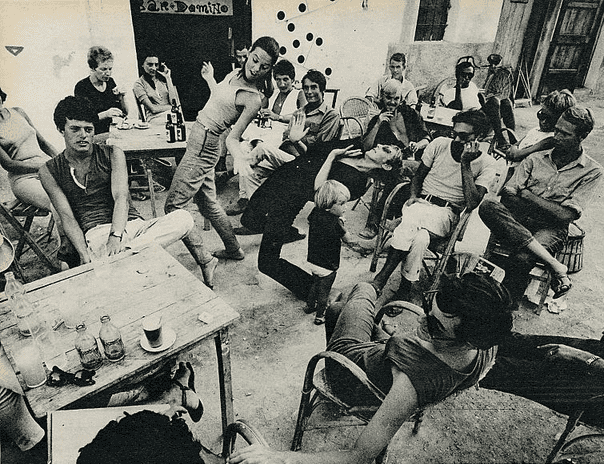

One of the first epicenters of the beatnik scene was the Domino Bar in Ibiza Town. Opened in the late 1950s near the harbor, the Domino was a scruffy harbor-side joint where the cosmopolitan mix of expatriates gathered nightly.It was run by a motley trio – a French-Canadian (Alfons Bleau), a German (Dieter Loerzer) and an Englishman, Clive Crocker – and became the gathering place for writers, artists, drifters and dreamers. Crocker, who had arrived in 1959, openly described himself as a “beat”, inspired by reading Kerouac. In true beatnik style, he and his companions spent the day in existential debates and long games of chess, and the nights immersed in jazz, cheap wine and the occasional joint or sugar cube of LSD. The bar’s record player (one of the only amplifiers on the island) played a soundtrack of American jazz – John Coltrane, Chet Baker, Billie Holiday, Charles Mingus, etc. – that gave Ibiza an unlikely bebop vibe. In Enright’s words, “jazz was pouring out of the one amplifier…it was jazz jazz jazz jazz jazz in anyone’s house,” which contributed to the scene’s heady atmosphere.

Domino Bar, (right) inside and (left) at the terrace. [Source]

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a wide variety of characters passed through Ibiza. Several American writers made the island their temporary home -among them Clifford Irving, Harold Liebow, Steve Seeley and John Anthony West- “many of whom documented their stay on the island” in memoirs or fiction. Irving, for example, arrived in the 1950s and stayed for two decades, later gaining notoriety for his Howard Hughes hoax, but also writing novels inspired by the people of Ibiza. From further afield came Janet Frame, the New Zealand novelist who found inspiration in Ibiza, and Damien Enright, an Irish writer who arrived in 1960 and would recount the era in his memoir Dope in the Age of Innocence. Enright was both observer and participant – he was even involved in a famous smuggling adventure; and he later described Ibiza in 1960 as “beyond the reach of imagination,” a tropical bohemia come to life.

Not all were literary; there were also artists and intellectuals among the first expatriates. In 1959 the Ibiza 59 Group was formed, an avant-garde artistic collective of European and American painters settled on the island. Its members included German abstract artists (Erwin Bechtold, Heinz Trökes and others), a Swede, a Spaniard and even an African-American painter, all attracted by the light and solitude of Ibiza. These artists predated the true “beatnik” influx, but they helped cement Ibiza’s image as a creative paradise. In fact, one scholar points out that many foreign artists, writers and intellectuals in Ibiza in the 1950s “belonged to the beatnik universe,” laying the groundwork for the hippie wave that followed.

Well-known visitors and beatnik personalities

The Ibizan scene of the sixties featured an eccentric mix of notables from the worldwide Beat movement. One of them was the Danish duo Nina and Frederik, a pair of folk singers who were also Baron and Baroness van Pallandt. Known for songs like “Listen to the Ocean,” Nina and Frederik perfectly embodied the international beatnik jet set: bohemian in style but aristocratic by birth. In 1960 publicity photos, they sported matching black turtleneck sweaters and carefree smiles, looking every bit the elegant beatnik troubadours. The couple performed throughout Europe and resided frequently in Ibiza in the early 1960s. Their story took a strange turn later in the decade – Frederik van Pallandt even used his yacht to smuggle marijuana – underscoring how intertwined Ibiza had become with the drug culture of the time.

Another colorful character attracted to the island was Christa Päffgen, better known as Nico, the German singer and model who became Warhol’s muse. After a small role in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, Nico moved to Ibiza with her mother in 1960 and bought a house on the beach. For a time she had a tempestuous affair with Clive Crocker of the Domino Bar. Nico’s presence added a touch of underground celebrity to the scene: she would later gain fame as a singer with The Velvet Underground, but in Ibiza she was just another bohemian embracing island life.

Ibiza also attracted established figures in British culture. Actors Terry-Thomas (known for his gap-toothed comic roles) and Denholm Elliott visited and resided on the island in the early 1960s. Their presence blurred the boundaries between high society and counterculture: they were genuine movie stars mingling with barefoot beatniks and local fishermen. English writer Laurie Lee, who had fought in the Spanish Civil War, also visited them. After a trip in the 1950s, Laurie Lee wrote about “playing dice and drinking bad wine” on the ferry to Ibiza and observed how the influx of foreigners was already changing the island, with each nationality forming its own expat enclave. His observation was prescient: in the 1960s Ibiza became a veritable cosmopolitan mosaic, a “Babel” of languages and cultures, as one Spanish author later described it.

Some notorious characters also arrived in Ibiza. Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory, fleeing legal problems elsewhere, settled in Ibiza in the early 1960s. He threw lavish parties and sold fake Picassos to gullible tourists until his story was immortalized in Orson Welles’ film F for Fake. Through de Hory, the Ibizan bohemians became acquainted with writers of the stature of Clifford Irving (who befriended de Hory and later plotted the Howard Hughes hoax) and even Orson Welles himself.

Not all of Ibiza’s notable “beats” were famous in a traditional sense. Some were legendary within the subculture. The Dutch poet Simon Vinkenoog, a key figure in Amsterdam’s counterculture, spent a stint in Ibiza around 1961, but his colleague, the famous writer and artist, Jan Cremer satirized him as a self-proclaimed guru leading pot-smoking sessions on the beach. Cremer’s account (which disguises Vinkenoog as “Simon the Soggy Noodle”) pokes fun at the earnest budding hippie, instructing him on how to look stoned and blurt out “love, love, love” in order to “look cool.” This humorous anecdote, published in Cremer’s autobiography, Barbaar Op Ibiza, offers a rare glimpse of the early 1960s Ibizan scene from a participant’s perspective.

Photo of the writer Jan Cremer, during his stay in Ibiza.

Jan Cremer, in turn, came to Ibiza by chance, a story that repeats again and again throughout the biographical history of many visitors of that time. In his autobiography, he describes himself as “destitute” at the time, but happy to leave “oppressive Holland” behind. Gallery owner Ivan Spence provided him with accommodation and some money to work with. This leads to an unprecedented creative outburst: at the opening of his first exhibition in Ibiza, practically all his works are sold. Cremer decides to stay on the island and starts working there in 1962 on the book that marks his breakthrough as a double talent: Ik Jan Cremer, the relentless bestseller that shook the culture of his homeland Holland.

Life on the Island: A Clash of Cultures and Influences

For the beatniks, Ibiza was idyllic: a “Casablanca of the mind” where “madmen” from abroad lived out their fantasies in a picturesque Spanish fishing village. They reveled in the laid-back atmosphere: days were spent lounging or creating art, and nights were spent exchanging poetry and philosophy over bottles of local wine. Marijuana was available (if you knew who to ask), and by the early 1960s even LSD had made inroads, reportedly introduced by a Dutch contingent led by Bart Huges – famous for advocating trepanation – who camped near the beach at Platja d’en Bossa. Even before the hippie era began, Ibiza’s bohemians were already experimenting with psychedelics.

Ibicencos, for their part, watched with a mixture of tolerance, curiosity and occasional bewilderment. Ibiza in the 1950s was poor and largely rural; many Ibicencos were still recovering from the hardships of the Civil War and postwar rationing. To them, foreign beatniks seemed like exotic, perhaps even irresponsible weirdos: young people rejecting a modern society of prosperity (however illusory that prosperity might be) at a time when most Spaniards were struggling to escape poverty. As a result, interactions between the local population and the expatriate Bohemians were limited. Historians note that the native population and the hippies/beats “had little contact and different values,” making meaningful exchange rare. Many Ibicencos simply left outsiders alone, following a live-and-let-live ethic. Enright observed that locals hardly interfered as long as basic respect was maintained. Some enterprising locals interacted with the newcomers by opening guesthouses, bars or services for them, quietly kick-starting a tourist economy.

The Spanish authorities, for their part, maintained an ambivalent stance. On the one hand, the Franco regime’s press and some officials condemned the beatniks and, later, the hippies as “international hooligans” who threatened public order and hygiene. A 1965 government campaign entitled “Keep Spain Clean” was understood as an attack on the scruffy, long-haired youths arriving on the coasts. On the other hand, Ibiza’s leaders realized that the island’s growing bohemian mystique was good for business. By the late 1960s, local tourism promoters prided themselves on Ibiza’s image as an island of freedom, using the avant-garde art scene and hippie flea markets as selling points. As one study notes, Ibiza’s authorities “supported the artistic avant-garde and activities stemming from the hippie movement to… publicize [the island],” actively cultivating its reputation as a countercultural paradise. This helped to consolidate an “intangible cultural heritage”-a myth of Ibiza as a free-spirited paradise-that persists in the island’s brand image even today.

Culturally, the beatnik presence also left more subtle traces. Ibiza’s artistic heritage was enriched by the many painters and writers who settled there, some of whom left works of art and literature. As for fashion, an interesting footnote links Ibiza’s beatniks to the birth of the island’s iconic Adlib style, the white cotton garments that today are emblematic of Ibizan boho-chic. According to local lore, German designer Dora Herbst launched the Adlib fashion movement around 1970. The idea of all-white, free-flowing clothing probably came after seeing a pioneering American beatnik couple in 1963 who dressed head-to-toe in white “symphony-in-white” outfits. Apocryphal or not, the story highlights how local entrepreneurs absorbed the eccentric style of the bohemians and reinvented it with a touch of glamour.

“Beatnik Central”: Ibiza in the mid-60s

In the mid-sixties, the word was spreading in European underground circles that Ibiza was “beatnik central”, a permissive playground for those looking for a “go” and a cheap life. What had been a small group of intellectuals became a wave of young adventurers. Summer brought with it an influx of transient beatniks, and soon the beat scene evolved into the hippie scene as the broader countercultural currents of the decade reached the coast. “As the decade progressed, beatniks became hippies,” writes one Ibiza chronicler, noting the influence of LSD, Eastern mysticism and the anti-war movement on the newcomers. In 1966 and 1967, Ibiza was already a well-worn stop on the “hippie route”: for many traveling from Western Europe to India (or vice versa), Ibiza was a convenient and idyllic stopover, being “as close to Algiers as to Barcelona,” making it a gateway between Europe and North Africa. A contemporary observer recalls that Ibiza became one of the three main hippie destinations along with Tangier and Goa.

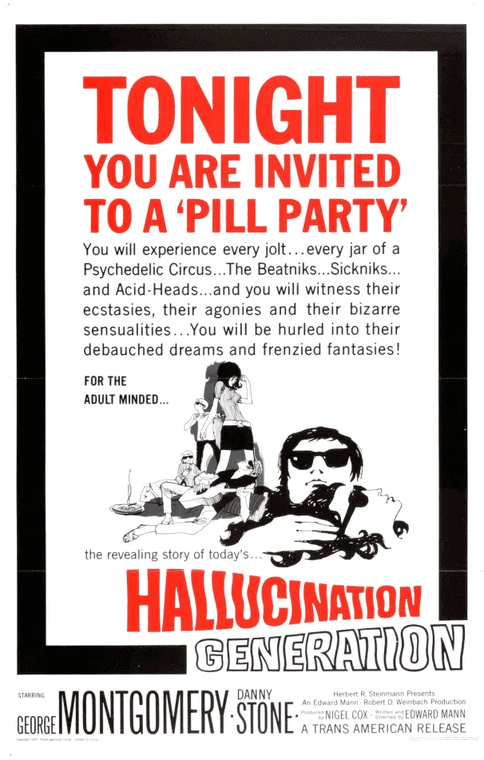

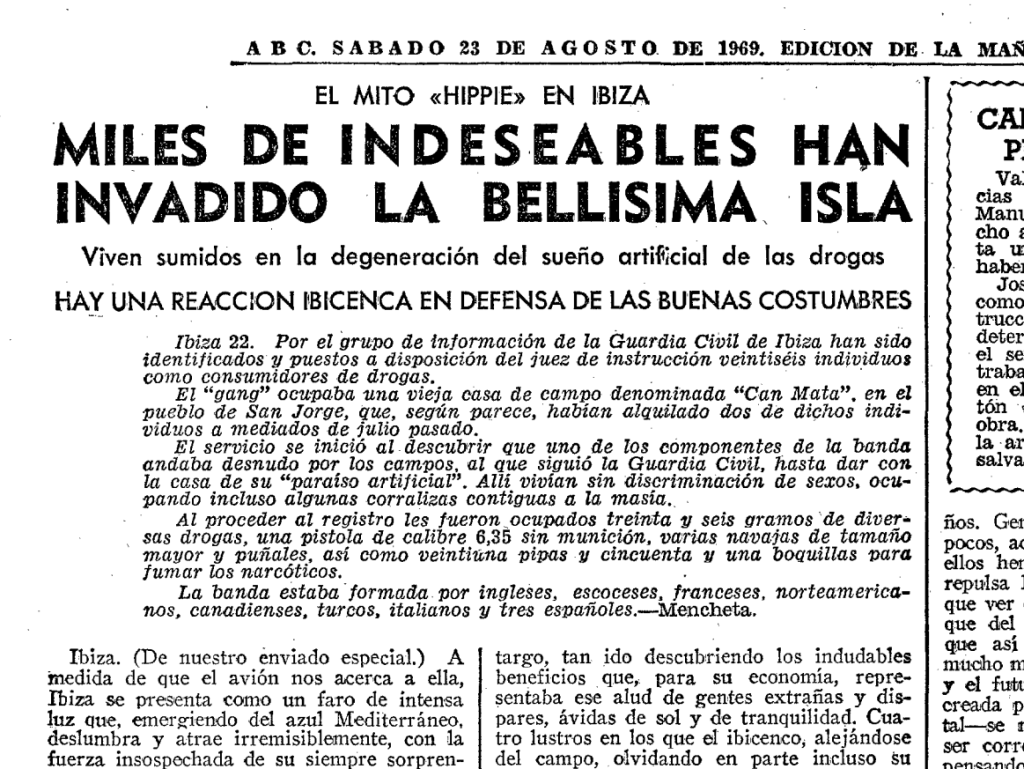

The media also took notice of Ibiza’s burgeoning counterculture. In 1966, a low-budget American film called Hallucination Generation was shot in Ibiza, exploiting its reputation as a haven for beatniks and experimental drug users. The film (for “adult minds,” its poster advertised) promised audiences an immersion into the “psychedelic circus” of Ibiza’s youth, with “beatniks, sickniks and acid-heads” indulging in “unbridled dreams and frenzied fantasies.” The poster’s lurid invitation – “Tonight you are invited to a pill party…” – enhanced the island’s wild image. Although a B cartoon, Hallucination Generation is evidence of Ibiza’s notoriety in the mid-1960s. Even Spanish newspapers of the time published alarmed articles about the “new plague” of beatniks, especially when larger groups of hippies began camping on the beaches at the end of the decade.

Headline of a Spanish mainstream publication, in 1969.

However, despite the growing influx of hippies, the original Ibizan bohemians remained a distinct and smaller group, what one local historian called the “genteel” artistic community, suddenly outnumbered by a less cultured and more rowdy hippie crowd. Carolyn Cassady, an American writer who knew the beats, visited Ibiza years later and bluntly commented that “the hippie movement was stupid” compared to the beatnik intellectual scene. “The hippie movement was a vulgarization…of the Beat movement, but with more light, sound and color,” wrote a Spanish academic, quoting the sardonic assessment of an Ibizan artist. Indeed, in 1968-69, many of the original beatniks either blended in with the hippie wave or left, as in their eyes Ibiza was no longer the “secret, quiet haven” it had been.

Legacy and sources on the beat era

The Beatnik era of 1950s-60s Ibiza, though relatively brief, had lasting consequences for the island’s cultural identity. It established the enduring brand of Ibiza as a bohemian getaway, a place where conventions fall away at the water’s edge. Many of the activities and images that are synonymous with Ibiza today – craft markets, art galleries, chill-out music sessions, holistic living – can be traced back to this period or the hippie continuation of it. As scholars have pointed out, the intangible cultural heritage left by artists, beatniks and hippies became a crucial part of Ibiza’s tourist attraction and local culture.

Fortunately, a large number of sources allow us to reconstruct this chapter of Ibiza’s history. Some of the main testimonies come from the literature of the time. Spanish novelist Rafael Azcona wrote Los Europeos (“The Europeans”, 1960), a novel set in Ibiza in the late 1950s that parodies the parade of foreign bon vivants and libertines on the island at the time. Likewise, Hombres varados (“Stranded Men”, 1960, p. 1963), by Gonzalo Torrente Malvido, vividly describes the decadent youth of Ibiza: “a drifting youth given to alcohol, leisure and easy love… among tourists, artless artists and companions of foolish ladies”, as one critic described it. These novels by Azcona and Malvido (recently adapted to film in 2020) serve as witty fictional snapshots of the Ibiza beatnik scene as seen through Spanish eyes of the time.

Memoirs and retrospective writings by foreigners provide further evidence. Damien Enright’s autobiographical book, Dope in the Age of Innocence, offers a first-hand look at 1960s Ibiza and the outrageous adventures (including drug capers) that unfolded. Some of Enright’s story has been shared in interviews, in which he wistfully details the wild freedom of those days, from the jazz-filled nights to the scams hatched with other expats. Other expats, such as Clifford Irving, Janet Frame and Laurie Lee, documented their Ibizan impressions in diaries, travelogues or later writings. Even the biting humor of Jan Cremer’s account of Ibiza’s “beatnik pecking order” is a valuable contemporary reference.

Ibiza’s own historians and lifelong residents have also preserved history. In local publications (for example, the book “El Nacimiento de Babel” – Ibiza años 60, by Marià Planells, 2002), interviews and recollections paint a vivid picture of the time. Writer Guillermo-Fernando de Castro recalled the arrival of what, in his opinion, were the first real beatniks in Ibiza: “a striking American couple” in the winter of 1963-64, the screenwriter husband and his remarkably “soap-averse wife Nora”, both always dressed in white. This same observer identified one Francisco Perez Navarro – a Spaniard who frequented Madrid’s literary cafes and periodically traveled to London – as “the first Spanish beatnik,” known for proclaiming that “the modern thing is not to bathe or brush your teeth.” Such recollections, though anecdotal, have been published and cross-checked with contemporary press reports, lending credence to the “vox populi” memory of Ibiza’s beatnik days.

In short, Ibiza’s experience with the Beat Generation was a unique intersection of time and place. During the 1950s and 1960s, a Spanish island isolated under a repressive regime improbably became a playground for the world’s disaffected creatives. The beatniks brought art, music and liberal ideas, and influenced everything from local fashion to the global perception of Ibiza.

In turn, Ibiza changed them: many found the inspiration they were looking for, others found infamy or tragedy, but few left without stories to tell. When the beatniks gave way to the hippies, and the hippies to the ravers, the cycle of countercultural renewal on the island continued. However, those early beat bohemians laid the groundwork. Today, as Ibiza markets itself as a free-spirited paradise for clubbers and yogis alike, it is echoing the real history forged by the beatniks who once danced under its stars and gazed at its Mediterranean sunrise with dreams of “On the Road” in mind.

Sources:

- Enright, Damien. Dope in the Age of Innocence (memoir) and interview in The Ransom Note

- Planells, Marià. El Nacimiento de Babel – Ibiza Años 60

- Ban Bam Ton Ton, “Looking for the Balearic Beat: Bohemians, Beatniks & Hippies” (2023)

- Stewart Home, “Ibiza in the Beatnik & Hippie Eras” (2009)

- Ramón-Cardona, J. et al., Land journal 11(1):98 – “From Counterculture to Intangible Heritage and Tourism Supply: Artistic Expressions in Ibiza, Spain” (2022)

- Spanish press archives: Blanco y Negro (4 May 1963); Diario de Ibiza (1966–67)

- Azcona, Rafael. Los europeos (novel, 1960); Torrente Malvido, G. Hombres varados (novel, 1963)