The relationship between psychology and architecture has become more relevant recently, in the last two or three decades. It is estimated that we spend on average 80 to 90% of our time indoors, including activities at home, at work, in schools and other indoor environments.

The study that addresses this question is psychological architecture or psychology of architecture (since there seems to be no consensus on a single term yet), and it starts from the thesis that the design of our spaces can directly and profoundly influence our mental and emotional well-being.

In this article we will explore how to use architecture as a tool to improve well-being and mental health, focusing on psychological architecture, its characteristic elements, how to apply it, some real examples and some variants or sub-branches, and then describe how to apply it in our own private home. The vast majority of these “recipes” are perfectly complementary to virtually any style and relatively easy to implement, even without building work in an existing house.

Psychological architecture

Psychological architecture or architectural psychology is an interdisciplinary study that examines how the built environment affects human behavior and mental health. This relatively recent approach considers elements of our environment such as light, color, space and acoustics, applying research in psychology, sociology and neuroscience to design spaces that promote, among other things, well-being and productivity.

This science is based on the principle that the human being is an “open system,” an interdependent complex that ranges from large-scale systems, such as the nervous, digestive and immune systems, to the internal metabolism of a cell. All exhibit a property called homeostasis, which is the innate ability of every cell in every complex organism to maintain a stable and constant condition, all by employing interrelated internal regulatory mechanisms.

The brain is an important regulator of all these systems (including the psychological system we call “the self”). From this point of view, “the self” could be considered a homeostatic mechanism that evolved to help us maintain equilibrium in our complex social relationships. Like all living complex adaptive systems, humans must cope with external ecosystems in order to survive. Many neuropsychologists believe that managing the interface between the internal experience of our body and the perception of the external environment is the main purpose of our brain.

For example, this article explains how in the 1990’s, Sentient Architecture faced a challenge in residential architecture: although clients offered their own criteria for designs, those same criteria often led to their dissatisfaction. By accepting these instructions without delving deeper, the architect was producing preliminary designs that did not meet the clients’ true needs, resulting in higher time and production costs, at best. Clients were disappointed and somehow unconsciously expected designers to “read their minds.” It turns out that the key to solving this problem lay in understanding that clients were not just looking for a building, but for an emotional experience, which required exploring the psychological and environmental associations that already existed in their minds.

Psychological architecture is based on a deep understanding of how spaces influence our emotions and behaviors. We can create environments that foster well-being and human connection by considering principles such as perception, memory, and sensory experience. These principles invite us to think about how every element of a space can affect our state of mind, creating places that we not only inhabit, but also inspire us and make us “feel at home.”

The fundamental principles of psychological architecture (theoretical):

– Perception: based on how individuals interpret their environment, the way spaces are designed can influence the perception of safety, comfort and functionality.

– Space and place: based on the relationship between physical space and people’s emotional experience, a design that considers the connection between space and sense of belonging can enhance well-being.

– Identity: architecture can reflect cultural identity. Spaces that resonate with people’s identity can foster a sense of community.

– Human behavior: designs that facilitate social interaction and mobility can enhance the lived experience.

– Emotion: as we have seen above, spaces can evoke specific emotions. The choice of colors, textures and shapes can influence the mood and overall experience of the inhabitants.

– Functionality: architecture should be practical and meet the needs of those who use it. Functional design improves efficiency and user satisfaction.

– Sustainability: by considering environmental impact and sustainability we can create spaces that are adaptable and durable.

In practice, the design that respects the above principles usually focuses mainly on the following elements:

– Natural Light: perhaps the most important element. Exposure to natural light has even been linked to improved mood and reduced depression. Although a balance must be struck, as overexposure to sunlight can also have counterproductive effects; for example, the problem in winter of large windows facing directly south and the stress that this can produce.

– Artificial light: in environments where natural light is scarce, such as in Northern European countries during the winter months, proper lighting can help combat fatigue and seasonal depression. Good lighting in the home promotes a cozy and relaxing atmosphere (see: Scandinavian-style lighting), encouraging moments of rest and connection with loved ones. By choosing the right artificial light, we can improve our quality of life, optimize our sleep and create spaces that inspire and motivate us every day.

– Shapes: soft lines and organic shapes (sometimes even eliminating corners) can evoke feelings of calm and well-being, while angular and rigid structures can generate a sense of tension or discomfort. The height of ceilings and the proportion of spaces are also factors that affect psychological perception.

– Open spaces: encouraging social interaction can help reduce the feeling of isolation. Similarly, an interior design with open and diaphanous spaces has also been found to have a positive effect on individual well-being.

– Colors and Textures: warm colors can create a cozy atmosphere, just as cool colors can create a more relaxing environment. The use of colors can also help define areas within a building, guiding people and creating a sense of order.

– Acoustics: Good acoustics, where sounds are absorbed, can create a more relaxing and comfortable environment, which can reduce stress and encourage concentration; whereas a place where sounds are reverberated or distorted can be distracting and uncomfortable. In addition, acoustics can influence privacy and intimacy; in offices or public spaces, proper acoustic design can help people feel safer and more comfortable talking, which encourages communication and collaboration.

It must be said that in many occasions these perceptions are subconscious; so, even if it is not something evident to us, external elements can induce sensations in us that we are not directly aware of.

One example of a building that was designed based on many of the principles of psychological architecture (and, among others, does not contain a single corner) is Maggie’s Centre, a café and social building in Leeds, England, conceived to be a place where patients and families of the attached hospital can recover good feelings.

Maggie’s Centre, Leeds, designed by Heatherwick Studio.

The Psychology of Color and Architecture

Color is a powerful element in architectural design that can influence people’s emotions and behaviors. Color psychology is used to create environments that promote well-being.

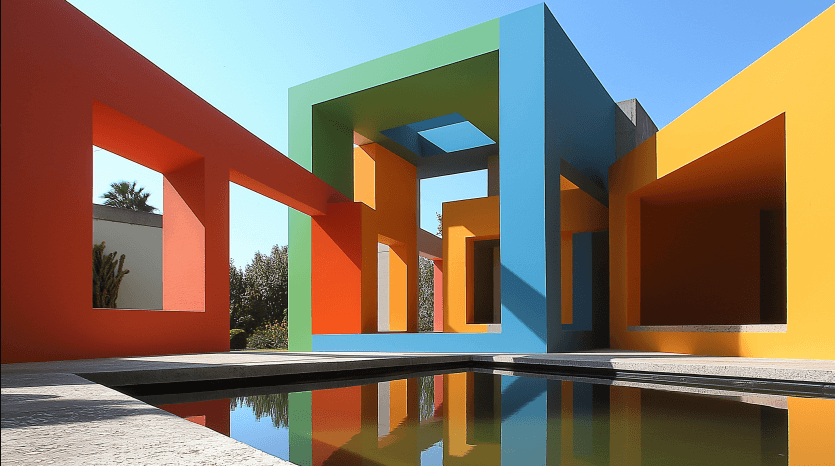

Emotional Architecture

With a special emphasis on colors, it is worth mentioning that there is a sub-branch or variant: emotional architecture, originated in Mexico by architect and engineer Luis Barragán. The differences with psychological architecture are subtle; since emotional architecture focuses on how built spaces can evoke feelings and experiences in people and seeks to create environments that foster positive emotions (such as happiness, calm or inspiration), mainly through elements such as light, color and the arrangement of space, while psychological architecture focuses its study on a more holistic plane, how the environment affects the behavior and perception of people, also considering aspects such as functionality, ergonomics and acoustics, among others.

Warm and Cool Colors

Depending on their temperature, colors can have an influence in one way or another:

– Warm colors: shades such as red, orange and yellow can evoke feelings of energy and warmth, but can also be overly stimulating if used in large quantities.

– Cool colors: shades such as blue and green tend to be more relaxing and can help reduce anxiety, making them ideal for workspace environments, but excessive use can also lead to lethargy or demotivation. Too much blue can evoke sadness or melancholy, while too much green can be overwhelming.

Creating Specific Environments

The choice of colors is not only based on aesthetics, but also on functionality and the emotional impact they can have on occupants. Here are some examples of how colors can be used to create specific environments:

– Learning spaces: In schools, the use of bright, cheerful colors in common areas can foster a dynamic and stimulating learning environment. Classrooms can benefit from a color palette that inspires curiosity and creativity, i.e., warm colors.

– Work environments: in offices, neutral and soft colors can be used to encourage concentration and productivity. However, more vibrant color accents can be incorporated in break areas to stimulate creativity and collaboration.

The importance of acoustics

Acoustics is an often underestimated aspect of architecture, but it has a significant impact on the occupant experience. Proper acoustic design can improve concentration, communication and overall well-being.

Acoustic design strategies

– Absorbent materials: Using sound-absorbing materials, such as acoustic panels and carpeting, can help reduce noise in public and private spaces. This is especially important in environments such as schools and hospitals, where noise can be a source of stress.

– Absence of corners: in a building can have a positive impact on acoustics by reducing the formation of unwanted echoes and sound reflections. Corners tend to concentrate and amplify sound, which can generate distortions and annoying noises. By designing spaces with curved shapes or continuous surfaces, a more even dispersion of sound is encouraged, which improves acoustic quality. In addition, these shapes can help minimize areas where sound accumulates, creating a more pleasant and comfortable environment. In short, a corner-free design can contribute to a better acoustic experience in a space.

– Space design: the layout of spaces can also influence acoustics. Creating quiet areas away from noisy areas can provide a haven for concentration and relaxation.

– Quiet zones: incorporating quiet zones in work and educational environments can give people a space to unwind and recharge, which is essential for mental well-being.

Intersection between sustainable architecture and psychological architecture.

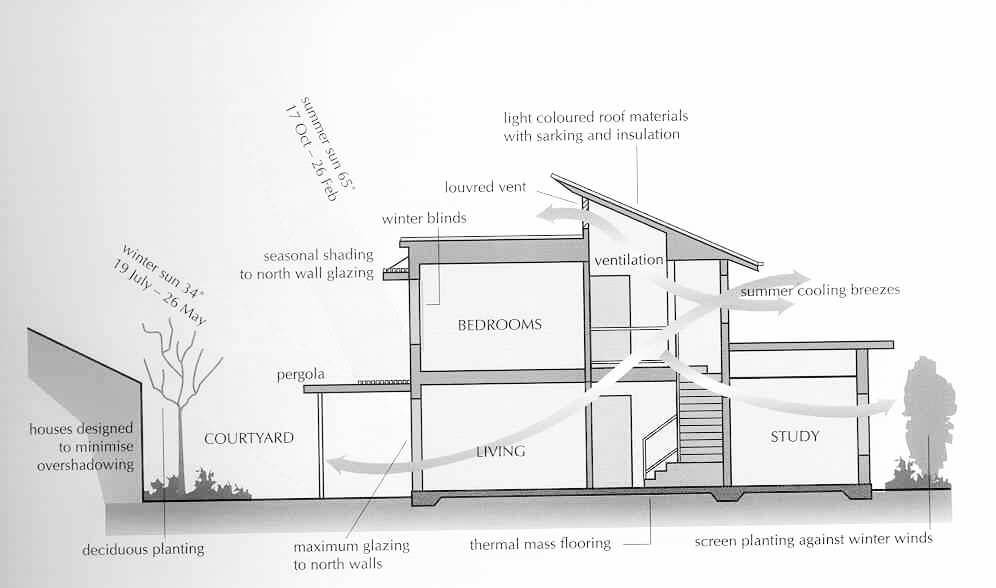

Interestingly, sustainable architecture not only has an effect on energy efficiency and reduced environmental impact, but also has a positive effect on the psychology of the occupants. These are the two most notable characteristics it can have in terms of its influence on the people who live in it:

Connecting with Nature

Incorporating natural elements into architectural design, such as large windows with outdoor views or vertical gardens, can improve mood and reduce stress. Green spaces, especially in urban settings, not only improve aesthetics, but also provide a place for recreation and relaxation. In addition, the use of sustainable materials in construction (which are usually natural as a rule) can create a healthier and more welcoming environment.

Energy Efficiency

Aside from the fact that economic savings on utilities can alleviate financial stress, design that considers thermal efficiency in balance with the natural climate can create a healthier and more comfortable environment. Well-lit and ventilated spaces that use natural resources effectively can improve the quality of life for their occupants, as natural sunlight and outdoor air (unless we live in the center of a city) are preferable to their artificial counterparts. Therefore, it can be said that energy efficiency in architecture not only reduces environmental impact, but can also influence mental health.

And this brings us to a related concept which, in turn, can be considered a variant or sub-branch of psychological architecture:

Biophilia

Biophilia refers to the innate connection that humans have with nature and can be considered as a key principle in psychological architecture or, in its more purist expression, perhaps even as an alternative branch.

In the context of architecture, biophilia translates into the design of spaces that integrate natural elements, thus promoting the physical and mental well-being of their occupants. This approach is based on the idea that proximity to nature can reduce stress, improve concentration and enhance creativity.

The incorporation of biophilia into architecture can manifest itself in a variety of ways. For example, the use of natural materials, such as wood and stone, not only adds warmth and texture to spaces, but also creates a more welcoming and healthy environment. In addition, designing buildings that maximize natural light and views to the outdoors allows occupants to feel more connected to their surroundings, which can have a positive effect on their mood. Vertical gardens, green roofs and outdoor spaces are other ways to integrate nature into architecture; they not only beautify the environment, but also contribute to sustainability by improving air quality and reducing urban temperatures. Creating spaces that encourage interaction with nature, such as patios and terraces, can encourage socialization and community well-being.

Studies have shown that biophilic environments can have a significant impact on mental and physical health. Exposure to nature has been associated with reduced anxiety, improved mindfulness and an increase in overall life satisfaction. In an increasingly urbanized world, biophilia in architecture presents itself as a valuable solution for creating spaces that nurture both people and the environment; especially in urban spaces it is starting to become a trend.

An example of this is the Fuji Kindergarden, built in Japan by Tezuka Architects, an oval-shaped kindergarten with a perimeter of 183 m, with a capacity for 500 children. It is conceived as a village in a single building. The interior is a softly partitioned integrated space with furniture. Three preserved 25 m high zelkova trees protrude through the roof.

Fuji Kindergarden, Tokyo, by Tezuka Architects. Photographer : Katsuhisa Kida

How to apply psychological architecture in the home

These principles can also be applied in the private home. To create an environment that is not only aesthetically pleasing and, in turn, promotes well-being and functionality. Knowing how to choose which general elements and features to apply in your own home is a combination of knowing yourself (or, in the case of the architect, knowing your clients’ preferences and lifestyle) and knowing what can be applied in a predefined space or home location.

Some strategies for integrating psychological architecture into the design of a home:

– Space Layout: An open design that connects areas such as the kitchen, dining room and living room can encourage communication and family togetherness. More intimate spaces, such as reading nooks or sitting areas, can offer refuge and tranquility. In this case, it is important to know people’s lifestyles, how they will move around and use the spaces, which can determine the range of preferences.

– Natural and artificial lighting: Natural light has a profound impact on our mood and well-being. Incorporating large windows, skylights or sliding doors that connect the indoors to the outdoors can maximize the entry of natural light. Daylight also regulates circadian rhythms, which can help improve sleep and energy. Similarly, well-applied artificial light can compensate for a lack of natural light, such as winters in Northern Europe or being in an urban space. For this, you can consult the solutions offered by the Nordic or Japanese style of lighting, or the fusion of the two, which seems to be a recent phenomenon that is on the upswing.

– Colors and materials: it is essential to select a palette of colors and materials that resonates with the personality and preferences of those who will inhabit the space. Warm colors, such as terracotta or yellow tones, can evoke feelings of warmth and comfort, while cool tones, such as blue or green, can convey calm and serenity. Likewise, the use of natural materials, such as wood and stone, can create a cozy atmosphere.

– Connection to nature: As we have seen, biophilia is a key principle in psychological architecture. By incorporating natural elements into the home, such as indoor plants or a focus on outdoor views, the emotional and physical well-being of the occupants can be improved. Plants not only purify the air, but also bring a sense of life and freshness to the space. Outdoor spaces, such as terraces or patios, can also be created to enjoy nature and encourage outdoor activities.

– Acoustics and silence: to create a serene environment, it is important to consider the use of sound-absorbing materials such as carpets, heavy curtains or, in more extreme cases, acoustic panels. If designing a building from scratch, you can also consider the absence of corners, even in some parts of the house. The home can also be laid out to minimize outside noise, by moving rooms away from noisy streets, and even create quiet zones, where moments of peace and reflection can be enjoyed.

– Ergonomics and furniture: furniture should be comfortable and functional. Ergonomics plays an important role in preventing injuries and promoting wellness; for example, chairs and tables at the right height can improve posture, while well-designed storage spaces can reduce clutter, feelings of chaos and underlying stress.

– Personalization and/or personal expression: Personalizing the space through artwork, photographs and meaningful objects can create a sense of belonging and emotional connection. In addition, allowing each family member to have a space that reflects their individuality can foster an atmosphere of respect and harmony.

– Technology and connectivity: the integration of technology in the home is a recent phenomenon and can also influence psychological well-being if applied for this purpose. Domotic homes” are an example of how many functions that were not even possible before can be automated and even made possible. To name a few examples, we have intelligent lighting systems, programmable thermostats and sound control devices that can help create an environment for more well-being. For example, the ability to adjust lighting based on time of day or mood can have a positive impact on energy and productivity. That said, we think it is equally important to balance technology with moments of disconnection, creating spaces where tranquility can be enjoyed without digital distractions; for example, network inhibitors could be used.

Applying psychological architecture in the private home involves considering how every element of design can influence the emotional and physical well-being of its occupants. From the layout of space and natural lighting to the choice of colors, materials and furnishings, each design decision can contribute to creating an environment that is not only functional and aesthetically pleasing, but also promotes mental health and overall well-being.

In fact, the vast majority of these principles can be applied regardless of architectural or interior design style preferences, unless very particular architectural styles are in direct contradiction (which is also the great exception). Many of these measures can be considered complementary, that is, it is not a choice between one style or another but to improve as much as possible within an existing framework, even in homes with very little room for variation, such as apartments or townhouses.

Here are two examples of homes that were conceived from scratch, taking into account most, if not all, of the principles of psychological architecture:

© Kelosa | Selected Properties. Villa by Blakstad for sale. You can visit the property here.

In this case, we see in the interior of this villa, designed by the popular local architect Rolf Blakstad, a clear example of priority for natural light, a strong presence of nature through the large windows, large open spaces and high ceilings, thick and insulated walls (for better acoustics), a prominence of natural materials and sustainable architecture (taking advantage of bioclimatic). In fact, the latter is an attribute drawn from the traditional architecture of Ibiza, on which the Blakstad style has been based since its origins, although modernized and adapted to modern needs and trends. Regarding the color, it is basically white (sensation of amplitude and space), which contrasts with the most used natural materials, wood and stone.

© Kelosa | Selected Properties. Villa Can Forestal en venta. Contacto para más información.

The following villa, designed by architect Bruno Erpicum, shows a very similar case, in terms of the aforementioned attributes, but thanks to being more minimalist cut, it expands even more the entrance of light, its impressive views and the amplitude of the interior spaces. The ceilings are still high, but the management of acoustics is solved with attenuating materials, there is a smooth transition between the interiors and the large terraces, it uses its location to take advantage of the bioclimatic of the place and the seasonal orientation of the sun.

Both villas are for sale through our agency and if you are interested, please do not hesitate to contact us here.

References – Sources:

A|sh.de:”Psychiatrie Trifft Architektur“(2022)

Wikipedia.org:”Artikelpsychologie“(2013)

Wirtschafts-Psychologie-Aktuell.de:”Die Macht der Räume auf unser Befinden und Erleben“(2022)

Sonderdruck aus Enzyklopädie der Psychologie:”Architektur und Psychologie“(2010)