The traditional rural house of Ibiza, also known as Ibizan finca, has been an object of study and fascination by many important people of several fields over time. What these first visitors found was an architecture that had hardly changed over the centuries, dated back to ancient origins. This was mainly because Ibiza, during most of its history, was a culturally and economically isolated society that had to use local resources and knowledge, the only ones available. The method of construction of this house came from a popular wisdom that was transmitted from generation to generation, pursuing subsistence and practicality. It was this practicality, together with simplicity, the functionality of each element and its integration into the landscape, which inspired about this unique archaic architecture and attracted the first visitors to this ‘remote island’ in the 1930s.

Among the architects who were drawn by the Ibizan farm house are Germán Rodríguez Arias or Josep Lluis Sert, from the GATCPAC group, or Erwin Broner, from the Bauhaus school. It also attracted well-known characters from other fields such as the Dadaist Raoul Hausmann, artist and photographer, who made a lot of photographs of these constructions, or the philosopher Walter Benjamin, writer and literary critic, who delved into his aesthetic theory attracted by the austerity and beauty of the Ibizan finca. Some of them spreaded this archaic architecture style in international exhibitions and, although the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the arrival of fascism interrupt the process, years later more scholars and artists continuously revisited and settled in Ibiza, motivated by this same fascination.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

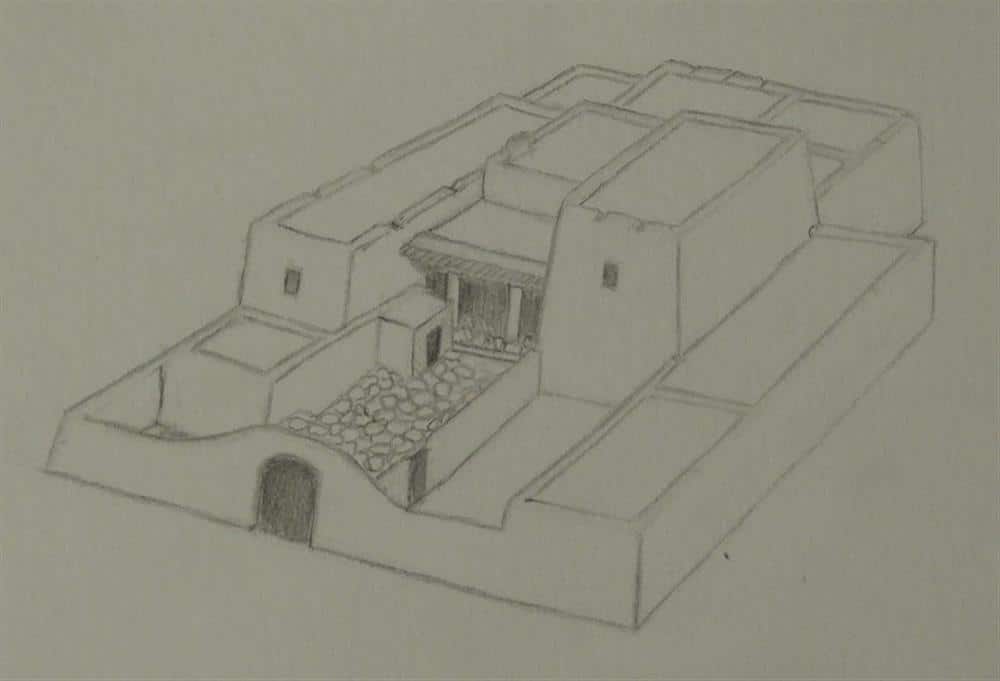

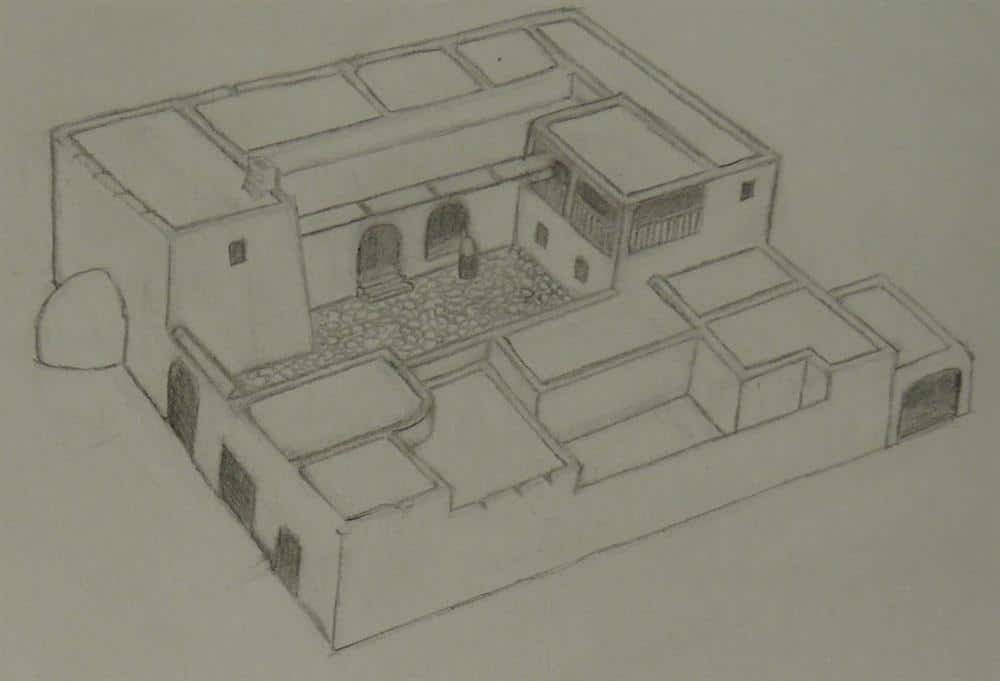

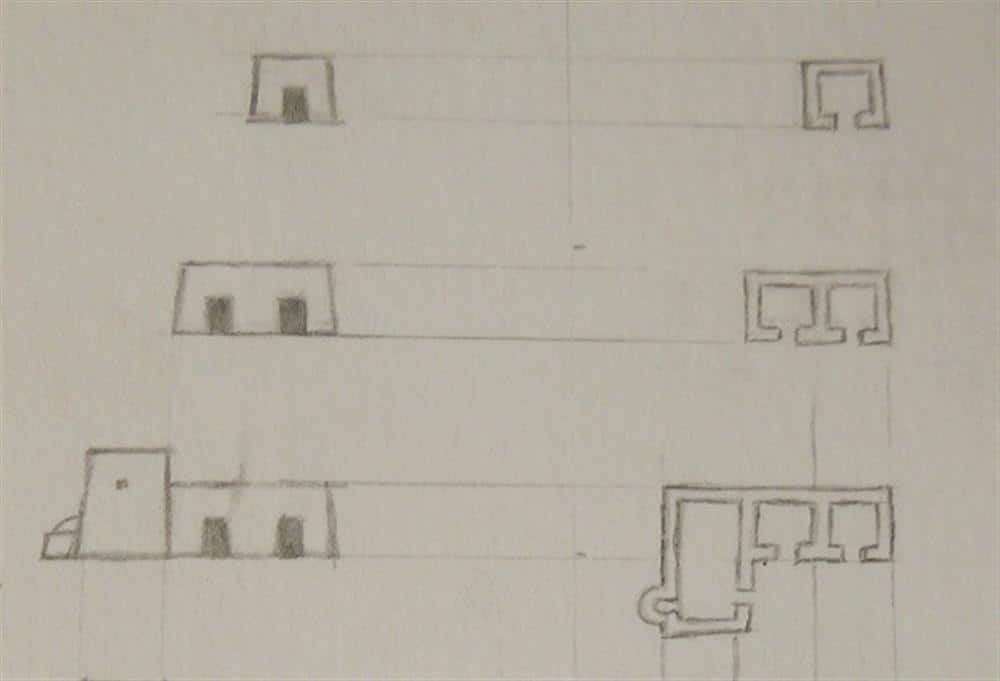

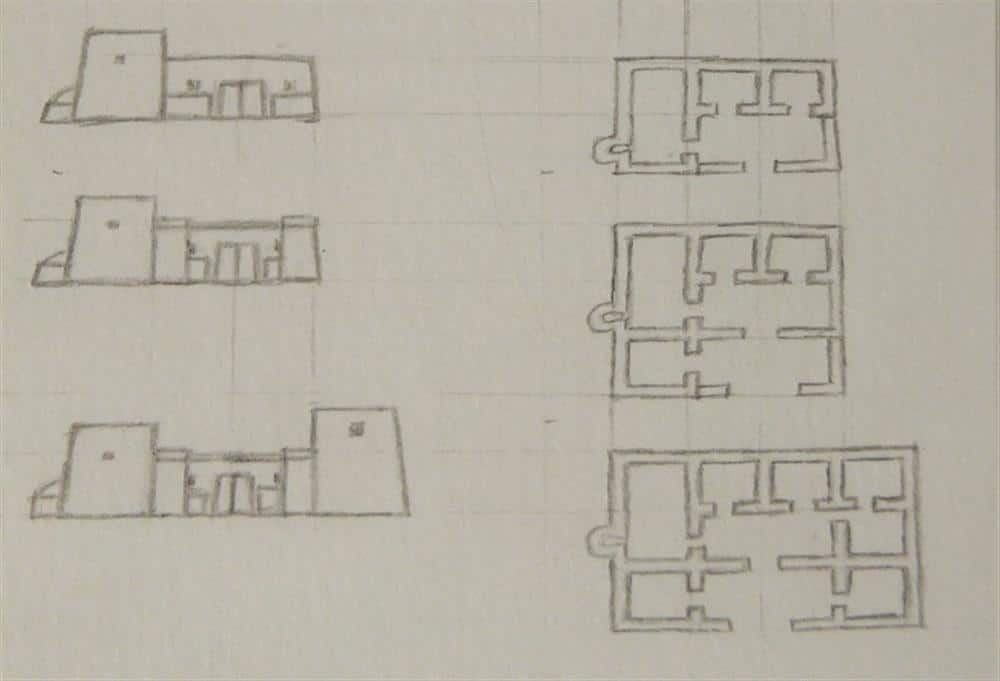

The Ibizan country house is defined by a building type of thick walls, composed of quadrangular modules and horizontal ceilings supported by wooden beams. It is a simple and sober architecture, which begins adding independent cubic modules that are articulated about a transverse rectangular space at the entrance, the main hall or porxo; each module has its own function and animal corrals are always separated from the main body. The whole set shows a fully functional home, often entirely absent of decorative elements, growing in relation to the needs of expanding the family or labour of the lands. It is also a continuously growing home, that at all stages keeps the appearance of a finished building.

Left to right: 1) Can Toni Martina, in St. Carles de Peralta. 2) Can Vicent Prats, in St. Antoni de Portmany. 3+4) General trend of enlargement

No Ibizan finca is ever the same as the other, what is common among houses prior to the industrial era, but all fincas have certain features in common that define them as an own architecture style. These general features of the original finca are:

Materials. Built by the farmer, it is essentially made of materials found in the same place: dry stone, juniper beams for the roof, sand, clay and marine plants.

Implantation. The house is ideally located on a high point of the side of a hill with rocks as natural foundation, taking advantage of landscape features and slope without overflowing on ground favorable to the cultivation.

Orientation. The entrance is almost always facing south, leaving behind the mountain, protected from the north winds and thus continuously receiving sunlight.

Absence of ornaments. It is shown as a primarily austere, practical and functional home, surrounded by fields and fully adapted to the needs of the time in which it was built. Subsequently, decorative elements would arrive such as arches and balustrades of carved wooden forms, but these were relatively discrete and concentrated on the main facade.

Prominence of the facades. The treatment of the facades reveals a clear hierarchy between the main facade, bleached, and the other facades, simply plastered or exposed stone walls. Similarly, the few decorative elements that can be found in the original finca are concentrated on the main facade.

The walls are wide, almost one meter, and consist of dry stone and mortar. Most walls are whitewashed in both homes and churches, although sometimes presented showing bare stone. The walls that enclose the building may have a form of steep walls (inclination and thicker at the bottom part) to strengthen the structure and the defensive function.

The windows are small and formerly had no glass, narrower on the outside than on the inside, thus emulating a fortress. Continuous attacks and plunders of vandals and pirates over centuries forced the homes to have this double function. Another purpose of the small windows was to protect the inside from the sun in summer, contributing to housing

The roofs are flat and originally made up of three layers: juniper wood, ash and marine plants and a layer of clay, which acted as insulation and impermeable. On rooftops different fruits of the field were sunned and serve to collect rainwater that is channeled through a cistern.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

The Ibizan finca is an consecution of adjoined and stacked cubic modules, shown as a construction of simple lines, flatness, enclosure, proportionality and human measures. Traditional Ibizan architecture finds its expression in the family house that is found in the rural environment of the island and, developing a specific typology, adapts both the terrain and the needs of its inhabitants.

The original distribution of these houses is a door that leads the main room (the porxo), public space of the house, the place of important meetings and transition between the outside and the private areas. The porxo is the acess to all the other rooms, generally the kitchen and two areas that originally served as both bedroom and storage. The kitchen, equal to or larger than the porxo, in ancient times also served to shield from the cold, around a bonfire on the floor, and as an occasional bedroom during winters. The front of the house was closed by a low wall, which inside multitude of herbs and a small orchard were kept protected from livestock. Separated from the main house were the pens that housed the animals. Surrounding to these were the fields, arranged in terraces of stone wall when they had to take advantage of the abundant slopes that the island has. Around some fincas there were also other architectural elements, such as a cart garage, oil mills, stables, lime kilns, the threshing floor or a coal deposit.

Ibizan Finca Distribution / Closed courtyard

In the original interiors of the Ibizan finca, of which today only memories and some photographs remain, is the same strict functionality and austerity as marked by the outside of the building. Most of the rooms do not have a defined function, such as the large porxo or the kitchen, that have multiple uses. The scarce furniture and the absence of decorative elements in every room of the house expresses a singular simplicity, a purely utilitarian sense that makes the architectural elements acquire a greater role. The main source of incoming light is in the porxo, but it doesn’t usually have more openings than the entrance door and, because of the small windows, this main room shows the same kind of gloom as found in temples.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

Especially the interiors, but also most of the outside of the Ibizan finca show a clear relationship with the Arab houses in rural areas, unlike the houses of Mallorca and Menorca, which rather resemble Catalan or Castilian country houses. Homes in Tunisia and Algeria are very similar to the Ibizan finca, as both show the same economy of means, adaptation to the environment, horizontality and composition of modules. In fact, his construction method is also found from the Himalayas through Yemen and the Middle East, to the south of the Atlas, and fits into a long tradition dating back to the Neolithic era. Several studies suggest that it develops in Phoenicia and Babylon, and later extends to the southern coast of the Mediterranean basin.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

Islands in the island.

Since ancient times, the people of Ibiza break with the two types of typical settlements of any other Mediterranean enclave: communities that prioritized defensive conditions by focusing on peninsulas or hills, and those that prevailed trade positioning its populations near the sea. Instead, cottages in Ibiza had a settlement scattered throughout the territory of the island and its distribution depended on the agricultural qualities (arable, fertile soil), being the distances between them irrelevant. This circumstances turned them into a kind of islands in the island.

The consequence of this unusual isolation was that these houses had to be self-sufficient from the outset and, at the same time, include elements that offered defense and shelter, such as thick walls or the praedial towers. Even the churches, which were conceived as fortresses and shelters inviting houses to group around it, failed to materialize real villages until recent times and this occured only partially, as evidenced by the dispersion of rural households that until nowadays are rarely grouped together.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

The dispersion of the habitat in Ibiza has been a constant since the Punic (Phoenician-Carthaginian) colonization. Throughout most of its history, the most profitable was to place the houses on the land they cultivated because arable soils were excessively separated. Even the Catalan conquest (1235) did not mean any change of habitat or cultivation method as they had for centuries with the Arab occupation.

Factors such as the isolation of the peasant houses, the low yields of their farms or the frequent pirate attacks led them not to rely on products and manufactured goods other than the basic, found nearby, pushing them to a near autarky situation. Therefore, homes and tools were made with the materials at hand, which explains the absence of building materials such as bricks or tiles. This dependency of the environment and the autarky of the peasant production unit are circumstances that explain the archaism of the Ibizan architecture.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

From these unfavorable circumstances and the farmers’ economic situation, close to subsistence for most of its history, adaptations took place in these constructions that surprise nowadays, considering it a model of sustainable and bioclimatic architecture. In this way, a climate of hot summers, little rain and wet winters and a mountainous landscape of scarce available land for cultivation, bring up the following adaptations to the buildings:

1. Environmental use and sustainability

Using the terrain rocks as natural foundation, the estate is built using materials found on the spot, without manufacturing processes rather than the mixture of mortar or lime kilns. In addition, the finca is ideally located on the slope of a hill, leaving behind the mountain, on a high surface with a slight inclination; which serves to prevent humidity and torrential rain, while being protected from the northern winds. The flat roofs are also used to collect rainwater that is channeled through a cistern for later consumption.

2. Bioclimatic

The thick walls and small windows insulate the outside temperature to keep the interior cool during the summer and warm in the winter, adapting the house to the climate of each cycle. The absence of glazing in the original fincas ensured the necessary ventilation for a perspiration of walls and roofs. The south-facing facades capture most of the sunlight in winter and more shade in the summer, while avoiding the winter winds from the north and allowing the entry of fresh winds in summer. Even the white of the walls had a role, by reflecting sunlight and prevent overheating of the building in summer.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

As could not be otherwise, the most interested in studying the Ibizan rural house were the avant-garde architects. In the 1930s it was a time of searching for new answers outside of classicism, towards new forms: rationalism, the Bauhaus and its heirs, Broner, Le Corbusier, the Group of Catalan Architects and Technicians for the Progress of Contemporary Architecture (GATCPAC), among others, found in Ibiza an architecture strongly shaped by climate, materials available and practically devoid of the influences of artistic or architectural styles from any given time, and the result of a direct contact between human being and the environment in which it developed its activity. In fact, the cubic simplicity of this ancient house was somehow a confirmation for those avant-gardist that the idea by them promoted was somehow on the right track, as it came countersigned by centuries of anonymous tradition developed on a small island, cradle of cultures.

The architects of the 30s described and embraced many elements of the traditional house, but did not have much interest in expanding their study into deeper topics like the historical origins of this architecture. A more extensive investigation would not appear until two or three decades later, and in particular two names are worth mentioning, that practically devoted their lives to studying this archaic architecture: the Canadian Rolph Blakstad, which is responsible for the first historical-typological study of the Ibizan houses, developing an important thesis about its origins, and later founded a new architectural style, modern but heavily influenced by the original finca; and the Belgian architect Philippe Rotthier, that apart from his extensive research on these buildings, carried out numerous rehabilitations of fincas and designed new buildings, rigorously faithful to the original old farms.

Comparative studies such as Blakstads and Rotthiers, published in books and articles, saw the ancient Phoenicians territories and their areas of influence in the Middle East, Mesopotamia and Egypt, the cultures that imported the construction method to Ibiza, dating its origin in the Neolithic. They also considered the Ibizan finca as the most faithful legacy of the ancient Punic houses and palaces that exists in the present day.

Through a comparison of plans and drawings of these publications shows the surprising number of constructive coincidences between the ancient architectures of Phoenicia, Mesopotamia and Egypt and the simple rural house of Ibiza. This theory is the most convincing to the majority, but it also encounters detractors within the research community. In fact, this is a topic that deserves an article by itself.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

Today the new fincas are built using other materials and have considerable differences in form and composition with regard to the original fincas. To adapt them to modern requirements, the new built fincas are differentiated by an expansion of virtually all spaces and rooms, creating an increase of incoming light and higher ceilings, some rooms merge into others and there is usualy a higher frequency of decorative elements, such as sloping walls, pergolas or pavilions, among others. These are the most common additions arising from new trends and possibilities offered by technological advances; however, in its essence, these houses bear a strong resemblance to the old fincas, as the basic geometry of its forms, the predominant white or the thick walls. The fundamental similarities that the Ibizan finca shares with minimalism also explain the tendency to combine these two styles.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

The scarcity of forms and decorative elements shown by the ancient fincas is a phenomenon that was conditioned by the precariousness and the necessary practicality, revealing that these homes were not meant to be seen, but to be lived. Its interesting how it is precisely this aspect that makes this style so popular nowadays, but mainly by the visual property of the design and less for the practicality for which it was conceived, although in many cases it remains practical.

However, until very recently the Ibizan rural house seemed to be detached from the process of transformation of history and was considered an archetype of popular architecture. Possibly it constitutes the last example of an age-old wisdom and an archaic form of life. Traditional Ibizan constructions were built without plans or specialization, but integrated into the same peer culture, it preserves the memory, the technique and the identity of a community.

Sources:

Rotthier, P. and Gobert, P. (2003). Treinta años en Ibiza, 1973-2003. [Sant Josep]: TEHP.

White, C. and Blakstad, S. (2012). Ibiza blakstad houses. Barcelona, Spain: Loft.

Ferrer Abarzuza, A. (1974). La casa campesina de Ibiza. Madrid: Narria. [consultado 10 de abril 2016]

Vilssa.com (2013). La casa ibicenca. Un ejemplo de arquitectura sostenible. [consultado 18 de abril 2016]

Mestre, B. y Torres, E. (1971). Guía de Arquitectura de Ibiza y Formentera, islas Pitiusas. Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Urbanismo. [consultado 20 de abril 2016]

González, M. (2015). El interior de la casa payesa. [online] Diariodeibiza.es. [consultado 5 mayo 2016]

Illesbalears.es (2009). Ibiza: edificios singulares. Institut Balear de Turisme. [consultado 5 mayo 2016]

Sharq, B. (2012). Las Casas Payesas, un camino a seguir. BK Rentacar. [consultado 10 de mayo 2016]

Kam, M. (2014). Edificación. Tipos de paredes y muros. Slideshare.net. [consultado 10 de mayo 2016]

Naya, C. (2016). Innistre. 1st ed. [ebook] Barcelona, pp.4-15. [consultado 12 mayo 2016]

It is possible that the pictures and the content reaches us through different channels and is sometimes difficult to know the author or the original source of the content. Whenever possible we added the author. If you are the author of any content (image, video, photography, text, etc.) and do not appear properly credited, please contact us and we will name you as an author. If you show up in a picture and think it impugns the honor or privacy of someone we can tell us and it will be withdrawn.

Kelosa Blog editors are not responsible for the opinions or comments made by others, these being the sole responsibility of their authors. Although your comment immediately appears in Kelosa Blog we reserve the right to delete (in case of using swear words, insults or disrespect of any kind) and editing (to make it more readable) or undermines the integrity of the site