Walter Benjamin was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century, known for his work in philosophy, literary criticism and cultural theory. He was an intellectual who stood out for his interdisciplinary approach, combining elements of aesthetics, history and sociology.

He is also recognized for his ability to connect ideas from different disciplines and for his unique style, combining cultural criticism with philosophical reflection. His interest in the impact of technology on art and culture, as well as his analysis of the modern experience, have made him a key figure in the study of modernity and critical thought in the 20th century. Some of his most outstanding works, such as “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” and “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, have left a deep mark on contemporary thought.

Small biography.

Walter Benjamin was born in the Berlin of the German Empire into a wealthy family of Ashkenazi Jewish origin. His father, Emil Benjamin, was a banker in Paris and later an antiquarian in Berlin, where he married Pauline Schönflies. Walter recalls that the stories his mother told him served as the basis for one of his theories: “the power of narration and of the word over the body”; it also made him reflect on the relationship that the stories established between tradition and actuality.

In 1912, at the age of twenty, he entered the University of Freiburg, but at the end of the second semester he enrolled at the University of Berlin to continue his studies in philosophy. There he became acquainted with Zionism, which his parents, having given him a liberal education, had not instilled in him. Benjamin did not profess orthodox religiosity; nor did he embrace political Zionism.

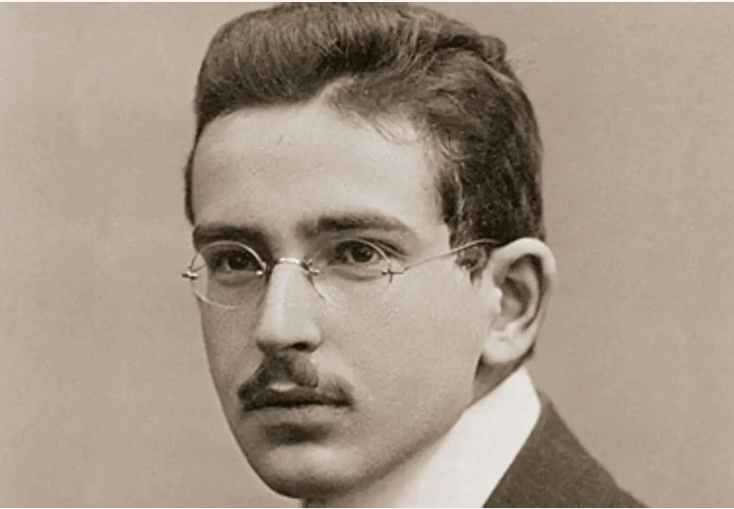

Source: Walter Benjamin Archive

During his university years he was elected president of the “Union of Free Students”, for which he wrote several papers on the need for educational and cultural reform. In his university years he had the courage to challenge the theoretical origin of the predominant formalism and wrote about his concern for language as a key piece of life: “Man communicates despite language, not because of language”; two ideas discordant with the established consensus of those times, for which he suffered in a way a double discrimination; as a Jewish intellectual and a leftist.

In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Benjamin wanted to enlist, but was not admitted due to health problems. However, after being deeply impressed by the suicide of two of his friends who were fighting, he ended up joining the pacifist current of the radical left, which rejected participation and collaboration with what they called an “inter-imperialist human carnage”.

In that year he began translating the works of Charles Baudelaire into German. A year later, in 1915, he enrolled at the University of Munich, where he met the poet and novelist Rainer Maria Rilke, and the philologist and historian Gershom Scholem. In 1917, he enrolled at the University of Bern, where he met the philosopher Ernst Bloch and Dora Sophie Pollack, writer and translator, whom he later married and had a son with. A little later, he had the project of founding a magazine, but it failed. In this period he also wrote a text in which he analyzed the concept of “myth”, and began a relationship with the theater director Asja Lācis.

He wanted to become a professor at the university, but was simply rejected because he was Jewish. He wrote The Origin of German Tragic Drama, where he worked on the concept of “allegory”; with which he brought to light the messianic conception of life.

At this stage he embraced materialism and set aside everything else, and here he affirmed his position before the trends of the moment: he never militated in Zionism, communism or fascism. For him, the salvation of humanity was linked to the salvation of nature. He was fascinated by the works of Marcel Proust and Charles Baudelaire, born observers of life. In 1926 his father died and he left for Moscow, where he wrote a diary and confirmed his theory about political tendencies, which caused to isolate himself completely. In 1929 he broke up his relationship with Asja and a year later his mother died. In addition, he was forced to mortgage his inheritance to pay his wife’s demands. It was a difficult period for Benjamin, but his romanticism always made him believe that it was the beginning of a new life.

Benjamin mercilessly criticized Hitler and fascist theory, as well as the “hypocrisy of bourgeois democracy” and the German financial and industrial capital that supported Nazism. He tried to reconcile Marxism with his Jewish cultural heritage and avant-garde artistic trends. His work focused on critical thinking, the critique of modernity and mass culture. His life was marked by the search for truth and understanding of the modern world, which led him to explore various currents of thought. Two World Wars and the rise of fascism shaped his perspective on society and culture.

However, his personal life was also marked by instability and the search for a refuge in the midst of chaos, probably influenced by the tumultuous events of his time. For that reason and the fact that the political situation in his home country of Germany was becoming increasingly dangerous for Jews and left-wing intellectuals, in 1932 he moved to Ibiza, which at that time was a place far from modernity and mass culture, anchored in the past, offering Benjamin an ideal respite and space for reflection.

At that time, he felt the need to flee from the great European metropolis to find tranquility in a place dominated by tradition and old customs, without a hint of modernity. In his own words: “The island is on the fringes of the movements of the world, even of civilization”.

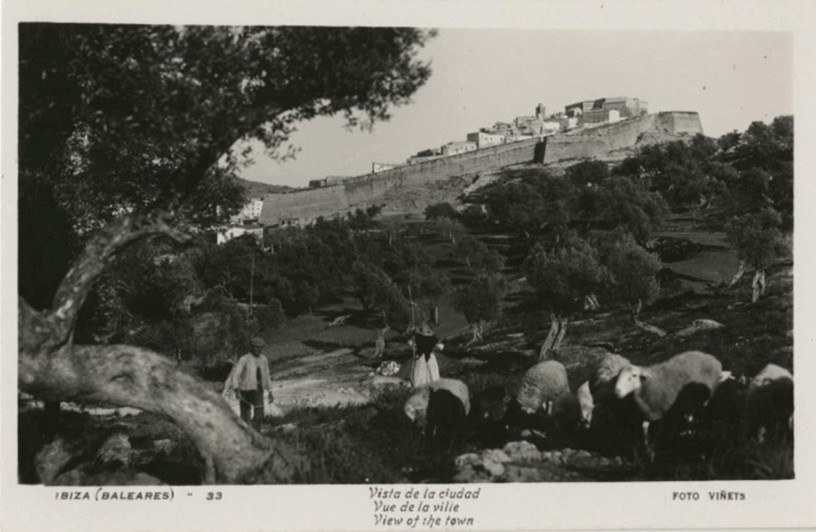

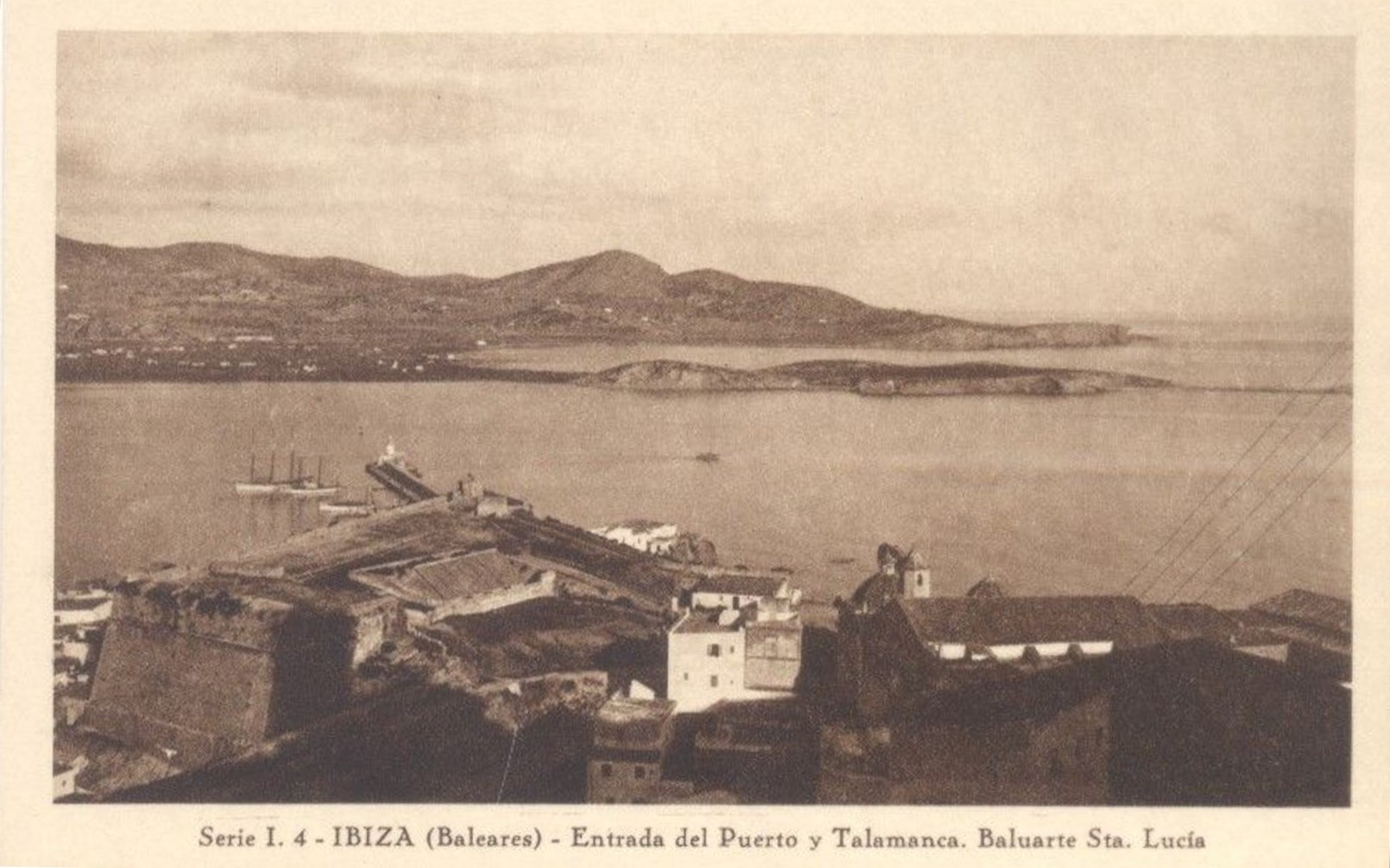

Old postcards of Ibiza. Source: Walter Benjamin Archive

Life in Ibiza was a period of intense intellectual production for Benjamin. Despite the difficulties he faced, he found on the island a place conducive to creation. In this context, Benjamin began to develop some of his most important ideas, which would later take shape in his most renowned work: “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”.

The arrival in Ibiza

Walter Benjamin had no clear notion of what awaited him when he decided to undertake his first trip to Ibiza in 1932. In Germany, the Weimar Republic, a democratic state that would be overthrown by hyperinflation and the Nazism of the Third Reich shortly thereafter, was in its final stages. In Spain, just a year earlier, the Second Republic had been established. Benjamin abandoned a relatively comfortable life in a large European city like Berlin to explore a remote and virtually unknown destination. The small Mediterranean island was on the prelude of tourist development, a place where modernity had not yet made its appearance, or anything like it.

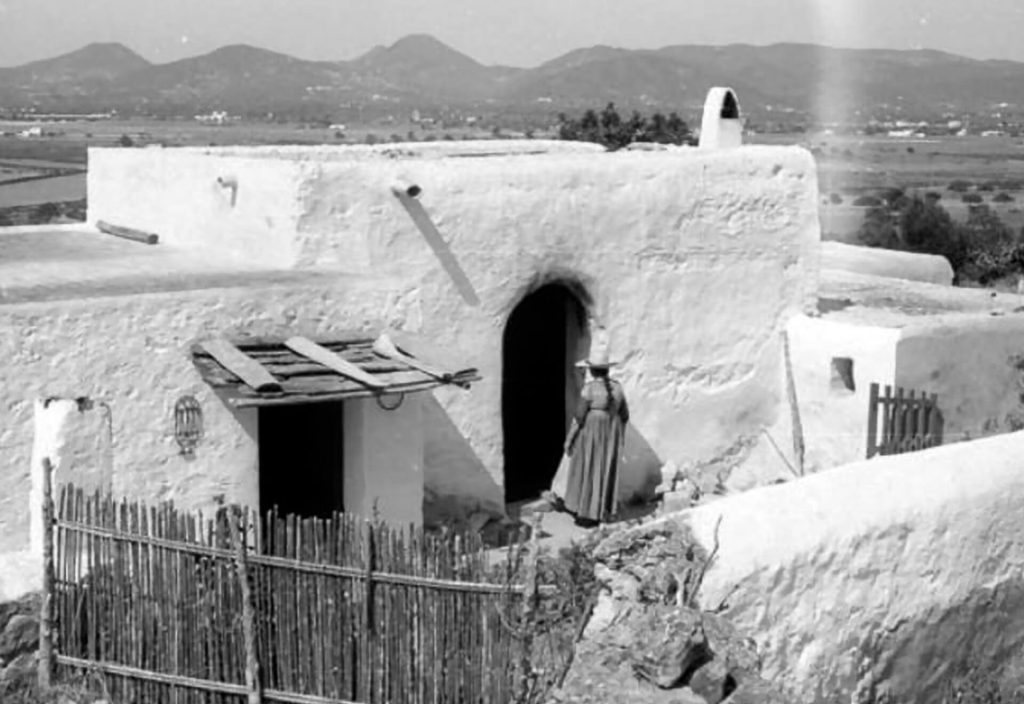

Photos from before tourism arrived in Ibiza. Left: Ibicencan finca / Right: Ibicencan family; special occasion or festivity dress

Benjamin lived in Ibiza at two intervals: from April to July 1932 and from April to September 1933. During these stays, the German philosopher went through several personal crises and developed a special bond with the island.

Ibiza was at that time an archaic place, which represented for a class of urban artists and writers the lost essence of a Europe that industrialization had made disappear from many places. Moreover, it was a very cheap place for foreigners and for Benjamin it meant being able to live from his collaborations in the press, radio and some literary projects, although without any kind of luxuries or “bourgeois comforts”, as he himself described in his writings and letters.

As beautiful as the island [Mallorca] is, what I saw there only strengthened my attachment to Ibiza, which has an incomparably more reserved and mysterious landscape. The most beautiful images of this landscape are highlighted by the glassless windows of my room.

-Letter by Walter Benjamin to Jula Radt-Cohn (1933).

As described by the Ibicencan writer Vicente Valero, in his book “Experiencia y pobreza. Walter Benjamin en Ibiza“:

“It seems that travelers visiting the island of Ibiza in the early 1930’s shared the rare sensation of discovering a truly unusual world. That unexpected experience was due above all to the untouched beauty of its landscapes, the primitive appearance of its rural dwellings and the customs of its inhabitants. Traveling to Ibiza was like traveling back in time. For various circumstances, not only geographical but also historical, Ibiza had preserved its ancient character, the inheritance received from different civilizations, the self-absorbed solitude of a community that remained faithful to its traditions and in which not a single one of the usual signs of progress had managed to enter. A strange but solid fidelity to the origins surprised, then, those travelers who, at that time, decided to travel to the island and began to make it fashionable.”

Benjamin arrived in Ibiza by boat on April 19, 1932. He was recommended by his friend Felix Noeggerath, philologist and translator, who had described the island as a place of “absolute tranquility” and with “incredibly low prices”. Upon his arrival, the Berlin writer realized that he had arrived at a place where “it seemed that time had stood still”.

From May, he stayed in an old house, close to the coast, located in the bay of Sant Antoni, next to an old mill that gives its name to the place: Sa Punta des Molí. This house adjoined a larger one in which the owner lived with his family. As Walter Benjamin described it: “The most beautiful thing about it is the view, which allows one to contemplate the sea from the window and an island of rocks whose lighthouse illuminates me at night”.

Walter Benjamin, in white, with the Selz’s in Ibiza.

Walter Benjamin devoted most of his days to reading and writing. He lived without running water or electricity, enjoyed bathing in the sea early in the day and taking long walks. The German writer described those landscapes as “the most unspoiled I have ever seen on habitable land”.

Ibiza was, in comparison with its neighbors Mallorca and Menorca, the poorest island of the Balearic archipelago; an economic factor that became an attraction for foreigners, who could live from their art without luxuries but with a certain solvency. For example, according to Benjamin, a stay cost between 60 and 70 German marks at the time, per month.

“It is understandable, therefore, that the island is on the fringes of the movements of the world, even of civilization, and that it is also necessary to renounce all kinds of comforts.”

-Letter from Benjamin to Gershom Scholem (1932).

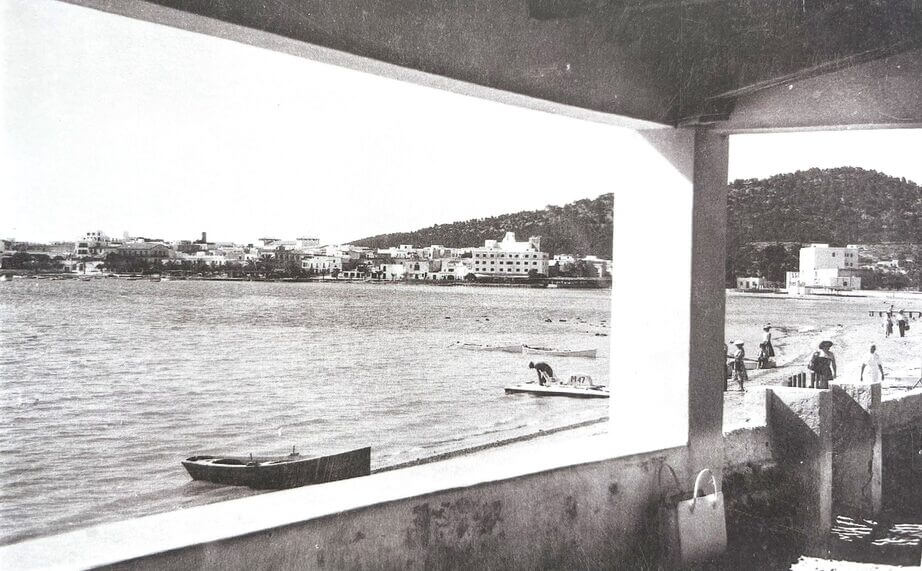

Port of Sant Antoni (1930s)

Benjamin lived in the village of Sant Antoni, one of the island’s population centers at the time. All the villages on the island consisted of a church, around which there were a couple of stores and a few houses. Unlike Mallorca and Menorca, the rest of the population of Ibiza lived in a dispersed way in the island’s territory, in the characteristic Ibicencan fincas, with a way of life based on tradition and subsistence economy. The peasants carried out agricultural and livestock tasks, made their own bread and wine, cut firewood, made charcoal and even hunted, among other activities; it was practically an autarkic lifestyle. An incipient bourgeois class began to appear, linked to the shipping companies and other manufacturing activities, but it was reduced and practically only in the port of Eivissa and in the citadel of Dalt Vila.

Bay of Sant Antoni (1930s)

What Ibiza was like when he lived there.

Between the twenties and thirties, two antagonistic worlds coexisted on the island for the first time: the older and the more modern. It was artists and intellectuals like Benjamin who helped to shape this “cultural myth” about Ibiza, based on the possibility of living “a different life”, in contact with nature and with a freedom that allowed the development of artistic creativity.

But, how was the coexistence between foreign and local intellectuals and artists? Again, Vicente Valero describes it in his book:

“Between 1932 and 1936, the island was visited by a good number of young people who aspired to be consecrated artists and professed noble anti-bourgeois ideals. Writers such as Albert Camus, Jacques Prèvert, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Rafael Alberti, María Teresa León, Josep Palau i Fabre and Elliot Paul, among many others, wrote about it in articles, books and poems. It was also in this way that the traditional Ibizan home became a symbol of both attitudes: it was, because of its location, a space conducive to artistic creation and it was also, because of its conditions, its structure and archaic typology, a space conducive to a life far removed from any bourgeois conventionalism.”

A group of travelers at the port of Ibiza.

It is well known that, both in the thirties and in the later wave of the sixties and seventies, a group of people arrived on the island whose lifestyles were practically antagonistic to the Ibicencan population. On the one hand, there were artists and intellectuals with strong countercultural and progressive tints, and on the other, a local population anchored in tradition and deeply religious. However, instead of a conflict caused by their strong differences and lifestyles, there was tolerance and peaceful coexistence.

In his book Vicente Valero also describes the origin of the “myth of Ibiza” that can still be interiores in the is isle today:

“The international myth of Ibiza, which had mainly in the hippie movement of the sixties its maximum promoter and spread, was created in the thirties by intellectuals and artists who made the island an alternative space, perhaps a little by chance, but a space where it was possible to write or paint freely, bathe naked, take hashish and, above all, feel interpreter of nature, in a kind of Arcadia lost and happily found.”

Before the great transformations brought about by construction linked to tourism development, the island stood out for the primitive appearance of its rural houses – whose architecture was very attractive to members of the Bauhaus School and the GATEPAC group– aswell as the ancestral way of life of its inhabitants.

The German philosopher was fascinated by this virgin island, impregnated with an archaic world that was about to be transformed forever. For him, the Ibicencan country house accurately defined the differences between pre-industrial modes of construction and the architecture of his time. He encounters a cultural and intellectual environment that arose around those traditional houses; as the landscape of Ibiza itself was, at that time, practically untouched.

The peasant houses were an architectural element that connected to ancient Ibosim, when the island was colonized by the Phoenicians, some three thousand years before. Benjamin used to criticize modern architecture for its functionalism and its disconnection with human experience. For the German philosopher, modern architecture transformed the living space by “dehumanizing” it, which also implied the loss of “the aura”; which, for him meant beauty, uniqueness and tradition.

From left to right: Jean Selz, Paul Gauguin, Walter Benjamin and fisherman Tomás Varó, sailing in San Antonio Bay (1933).

However, the threat of progress was present in what was only a foretaste of what Sant Antoni would become over the decades. During his first three months, Benjamin lived with intensity the experience of that ancient world in the process of dissolution.

In the first of his letters he writes to his friend Gershom Scholem, a few days after his arrival, in April 1932:

“It remains to be said finally that there is a serenity, a beauty in men – not only in children – and, in addition to that, an almost total freedom from strangers that must be preserved by the parsimony of information about the island… Unfortunately, all these things may be threatened by a hotel that is being built in the port of Ibiza.”

During his second stay, in a new letter to Scholem in June 1933, he writes:

“Now I take every opportunity to turn my back on San Antonio. If you look closely, in its surroundings, battered by all the horrors of the activity of its inhabitants and speculators, there is no longer a secluded corner or a minute of tranquility.”

While the letters and writings of 1932 Benjamin emphasizes the positive impression, generated by the beauty of the landscape and the possibilities it offered; in the letters of 1933, on the other hand, a tone of exhaustion and uncertainty predominates, produced by the personal difficulties of being an exile in conditions of poverty and an island that little by little increases its costs of living due to the increasing presence of tourists.

In those years, there were only two guesthouses in Sant Antoni, to which three more would be added in 1933. Work on the first, the Hotel Portmany, began in October 1931 and was completed two years later. 1933 was a key year for Ibiza’s tourism industry, since at the same time other emblematic establishments were inaugurated on the island: the Buenavista Hotel, the Gran Hotel and Isla Blanca Hotel.

Left: the first hotel in Sant Antoni, the year of its inauguration (1933) / Right: view of downtown Sant Antoni, towards Sa Conillera islet (1931)

Benjamin’s second period on the island was less happy than the first. He returned in April 1933, forced by the totalitarian climate in Germany. As he was a Marxist sympathizer and of Jewish origin, he was considered an two times enemy for Nazism. From September of the same year his health deteriorated. Benjamin suffered from infections, fever and general weakness; it was not until some time later that he learned that it was due to the malaria he had contracted.

In September 1933, he writes the following in a letter to his friend Gershom Scholem:

“The fact that I can barely stand on my feet, the impossibility of speaking the language here and the additional necessity of having to work as much as I can, drive me, at times, in such primitive living conditions, to the limits of the bearable.”

On September 26, he had to leave the island for good, bound for Barcelona, on his way to Paris.

Benjamin died, exactly on September 26, seven years later. The writer needed to leave France to travel to the United States. A year before World War II started, he was interned in a concentration camp in France, because he was a “non-naturalized German”. He was then interned in a French center for voluntary workers, but managed to get out of there with the help of influential French friends. On his way to the USA, he had to enter Spain first.

Guided by writer and activist Lisa Fittko, who helped many people escape from Nazi-occupied France, and accompanied by photographer Henny Gurland and her son, Benjamin arrived in Portbou on September 25, 1940. However, upon arrival, he was intercepted by Franco’s regime police because he lacked a required visa. His friend Adorno had helped him obtain transit visas in Spain and entry visas to the US, but he simply did not have a French permit to leave the country. His companions did get through to continue their journey.

Benjamin knew that if he returned to France he would be caught by the Gestapo, who were looking for him. He always traveled with a dose of morphine pills for desperate situations like the one he was in. As he wrote on September 26, 1940:

“In a no-win situation, I have no choice but to end it. I am in a small village in the Pyrenees, where no one knows me, where my life is going to end. I ask you to convey my thoughts to my friend Adorno, and to explain to him the situation to which I have been driven. I do not have enough time to write all the letters I wished to write.”

These were perhaps the last words of Walter Benjamin, one of the most brilliant and influential thinkers of the 20th century.

THESIS IX / “Theses on the Concept of History”, Walter Benjamin in 1940 (fragment from his last work):

“There is a painting by Klee called “Angelus Novus” depicting an angel contemplated and fixated on an object, slowly moving away from it. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth hangs open and his wings are outstretched. This is exactly how the Angel of History must look. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it at his feet. Much as he would like to pause for a moment, to awaken the dead and piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Heaven, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which he turns his back, while the heap of rubble in front grows sky-high. What we call progress is this storm.”

“The work of art in the age of its mechanical reproducibility” (his best known work):

The extraordinary thing about Walter Benjamin’s best-known book is that it is still the order of the day and has proven to be on the track of events long before reproducibility developed in its full form, as we experience today. It should therefore surprise no one that it remains a reference teaching material in high schools and universities; even beyond art, philosophy or sociology majors.

A couple of key ideas that appear in this work:

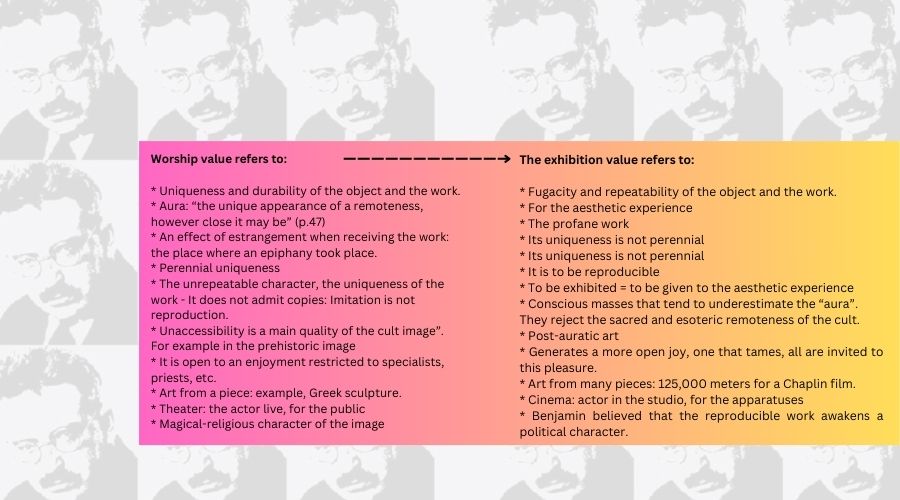

According to Benjamin, art would no longer be primarily auratic, that is, predominantly with a cult value, but profane art, in which the experience of the observer and the public exhibition of the work is more important than restricting it to specialists, kings, popes and bourgeois. The industrialization of images made art more accessible, less private, more profane and less sacred.

The Berlin writer comments that post-auratic art is an art in which the political overcomes the magical/religious. The work tends to cease to be a sacred and exclusive object, and begins to be a universally accessible object. The work of art in the age of technical reproducibility implies a displacement of the image from its cult value to an exhibition value. Before the industrial revolution the work belonged to a restricted enjoyment, reserved to the cult, to priests, nobles and specialists. In capitalism the work of art has a more open enjoyment, everyone is invited to this pleasure and aesthetic experience, as this little scheme shows:

Benjamin thought that avant-garde art and the technique of image reproduction would play in favor of the political awakening of the masses in a world in which social revolution would triumph. Pointing to this tendency was the fact that many works of art of the time clearly had “political ingredients,” leftist messages and demands against war and fascism. Certainly, works of art have the power to speak in “another language”; one that through the work exposes social and political injustices or criticisms.

The possibility of reproducing images, works, objects, speaks directly of industrialization and capitalism. Walter Benjamin says that it is a phenomenon that accompanies the rise of the masses:

“(…) to approach things is as passionate a demand of the contemporary masses as it is in their tendency to go beyond the uniqueness of each event through the reception of the reproduction of the same. Day by day, the need to seize the object in its closest proximity, but in image, and even more in copy, in reproduction, becomes more and more irresistible.” (P. 48).

The image makes it possible to bring closer what is far away, what one does not have, even what has died. Cinema is seen as an instrument of massive influence in Benjamin’s book, who sees in this art the possibility of acting as a psychic vaccine:

“(…) when one realizes the dangerous tensions that technification and its aftermath have generated in the great masses (…) one comes to the recognition that this very technification has created the possibility of a psychic vaccine against such mass psychoses by means of certain films in which the forced development of sadistic fantasies or masochistic hallucinations is able to prevent their natural dangerous maturation among the masses ” (P. 87).

In conclusion, Walter Benjamin was a fascinating person whose life and work continue to captivate people around the world. Through his unique perspectives and innovative ideas, he made important contributions to the fields of philosophy, sociology, and literary criticism. His ideas on the intersection of history, memory and cultural production have had a profound impact on fields such as cultural studies, media theory and urban studies.

From his early years as a student in Berlin to his exile in Paris and tragic end, Benjamin’s life was marked by intellectual curiosity and a deep passion for knowledge. His critical engagement with modernity and capitalism challenged conventional wisdom and offered alternative ways of thinking about society.

Walter Benjamin’s legacy lives on through his writings and influential ideas, and his work reminds us of the power of critical thinking and the importance of challenging established norms. His enduring influence and intellectual prowess make him a figure worthy of exploration and study.

Sources:

ElDiario.es: “Walter Benjamin en Ibiza: de la fascinación por la isla virgen a exiliarse por el nazismo” (2023), by Nicolás Ribas

Lectura Abierta: “La obra de arte en la época de su reproductibilidad técnica: breve análisis” (2017), by Julián Bueno.

Cultur Plaza: “Otra Ibiza es posible, gracias a Walter Benjamin” (2018), by María Jesús Espinosa de los Monteros.

Meer: “Los días de Walter Benjamin en Ibiza” (2021), by Virginia Serra.

Salvem Sa Badia: “El Hotel Portmany, historia de un alojamiento pionero que trajo a la bahía el turismo más selecto” (2022)