Vernacular architecture has evolved over many years to address the inherent problems of housing. Through a process of trial and error, populations have found over the centuries ways to deal with the extremes of climate. However, the influence of Western culture is omnipresent and the tendency to an internationalized construction style has resulted in a reduction of traditional solutions.

Logically, modern inhabitants demand higher standards of comfort in their homes. Such standards can be achieved through the use of machinery like air conditioning systems, which have considerable initial costs and an even greater energy demand in the long-term. However, with the careful use of traditional techniques it is possible to create thermal control improvements, since there are clear advantages to drastically reduce energy needs and a greater use of architectural style can create a more pleasant living space.

Fallingwater, by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1934) /Photo: Carol M. Highsmith (public domain)

This does not mean that designers should imitate the paths of the past. Modern materials, technology and innovative construction techniques should be used in the search for efficiency and profitability. Despite this, ignoring our architectural heritage and overlooking the accumulated wisdom of the past involves neglecting the inevitable challenge for greater energy efficiency need in the s. XIX.

The wisdom of popular construction provides us with the protection of unfavorable climatic conditions and achieve a comfortable microclimate are the primary objectives of this architecture, as well as design buildings that are in harmony with the harsh climates of its various regions.

In traditional architecture, the internal thermal regulation mechanism is incorporated in the building itself. It takes into account the topography, construction, morphology, even the layout and use of internal spaces participate in the function of the mechanism of thermal regulation.

However, internal conditions abstained considerably from the current comfort requirements. Rapid and spectacular advances in the technology of heating and air-conditioning installations for refrigeration, as well as other technical innovations and international design influences, have displaced the architecture of traditional values and principles.

Mechanization and internationalization led to the rejection of traditional methods and the lack of knowledge of the physics of construction deprived the structure of the building from its basic skills and left it at the mercy of the climate. Modern buildings have become climatically inept, with air conditioners replacing natural cooling, assuming a high energy consumption, as well as a cost reduction for construction companies and a huge profit for the energy industry.

Submission of architecture to the machine also leaves some problems of basic comfort conditions in the interior unresolved; such as cost problems, maintenance of mechanical facilities or energy over consumption. In Great Britain, for instance, buildings have shown to absorb a huge percentage of total energy consumption that reaches up to 50% of total on average.

Fossil fuel scarcity, as well as the growing degradation of the environment, have awakened the interest of the use of more ecological materials, processes and energy sources and has made it necessary for our modern buildings to provide shelter with the least possible expenditure of energy.

Casas Bioclimáticas ITER – Sur de Tenerife

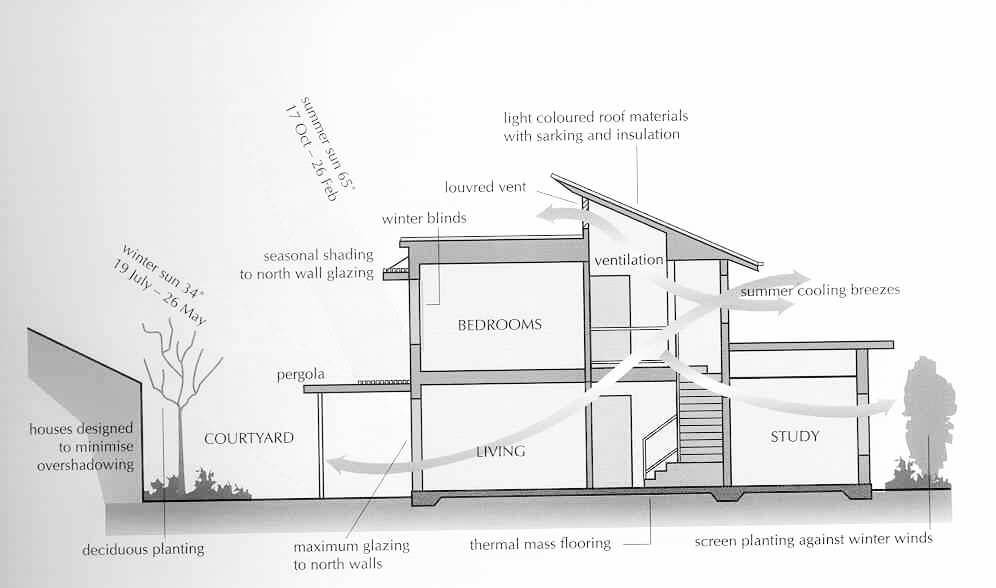

This gave rise to a new approach to bioclimatic architecture, which considers the building as a whole from the beginning stage as a place of energy exchange between the interior and exterior, the natural and climatic environment. Consider the building as a living organism; a dynamic structure that uses the beneficial climatic parameters (solar radiation for winter, sea breezes for summer, etc.) while avoiding the most adverse climatic effects. In this approach, the mechanical systems are integrally interconnected with the architecture and must be taken into account as fundamental elements of the building.

This new approach seeks to evaluate the energy demands for heating and cooling in buildings, first of all analyzing the free energy systems that are available. The preliminary analysis of bioclimatic terrain graphics for architectural design allows to outline strategies for an appropriate building location in any season of the year, which could considerably reduce the energy cost and minimize the need for mechanical means, while considering high standards of modern comfort criterias.

It is clear that the task of the modern architect is considerably more complicated than that of the ancient builders. The demands of modern life introduced new factors and considerations into the design of buildings beyond the relatively “basics” of the traditional lifestyle. As technology advances and life becomes more demanding, the judicious and optimal organization of complex variables that involve technical, social, utilitarian and cultural aspects, still converge in the creation of cosiness and convenience for the inhabitant. The priorities of the architect in the design process is therefore altered; machines become more important in the production of comfort standards. In addition, as the feeling of ‘comfort’ is a subjective perception, it varies from person to person from one culture to another and over time. Therefore, it is unfair and wrong to judge thermal comfort levels in traditional buildings for the same pattern we use for modern ones.

However, the tools, materials and techniques available to the modern architect are more than the indigenous builder could ever have dreamed of. In addition, the architect has the advantage of the accumulated knowledge of his predecessors. Through the union between the traditional viable approach to construction and the complex design criteria of contemporary practice, recommendations can be derived for maximum energy efficiency in the building.

In addition to these two main elements of traditional architecture that mitigate extreme weather conditions, the organization of spaces and their orientation, other architectural solutions that reflect traditional wisdom and are used in modern passive solar architecture are identified. These components are the varied designs of windows and their shading devices, such as blinds, screens, pergolas and overhangs.

Of these, the courtyard, the overhangs or side walls and the manually operated shutters were tested in a series of parametric optimization studies and it was discovered that the more complex houses with a U-shaped patio, save more energy than the simple forms. This was attributed to the additional factors involved in the thermal performance, with the introduction of carefully chosen parameters in the optimization studies that act as regulators in the house, such as the enclosing insulation and the orientation with more surfaces exposed to the south. It has become obvious that an effective pattern requires thermal studies for each building with its own geometry, configuration and particularities of an integrating design approach.

For the shading, it was concluded that the optimized design of overhangs and lateral walls, without shutters or blinds, could provide sufficient summer sun control to maintain thermal comfort inside. The application of blinds is often limited by a series of environmental, architectural, economic and behavioral design considerations. The solar control function could then be carried out as a secondary function and the blinds could be installed mainly, if necessary, for privacy or security. However, the conclusions of studies reinforced the belief that the intention of the inhabitants of the Mediterranean in regards to shading of the blinds was for the maintenance of interior comfort.

The passive responses of traditional architecture to local environmental conditions and influences represent a treasure trove of knowledge and information patterns for modern sustainable and bioclimatic architecture. Therefore, successful climate design should not ignore the accumulated experience and wisdom of our ancestors, but should develop after a deep understanding of the scientific knowledge, rather than an emotional assessment of traditional architecture. The architectural expression must respect regionalism and be based on a multidisciplinary design approach.

Mass knowledge and technology from modern industrial development should not be ignored either. Therefore, architecture must be a synthesis of both, the aspects that are in harmony with traditional values and at the same time adequate for contemporary societies, their cultural identity and human scale, based on appropriate technology.

References:

Serghides, Despina K. (2010). The Wisdom of Mediterranean Traditional Architecture Versus Contemporary Architecture – The Energy Challenge. The Open Construction and Building Technology Journal, 2010, 4, 29-38.

It is possible that the pictures and the content reaches us through different channels and is sometimes difficult to know the author or the original source of the content. Whenever possible we added the author. If you are the author of any content (image, video, photography, text, etc.) and do not appear properly credited, please contact us and we will name you as an author. If you show up in a picture and think it impugns the honor or privacy of someone we can tell us and it will be withdrawn.

Kelosa Blog editors are not responsible for the opinions or comments made by others, these being the sole responsibility of their authors. Although your comment immediately appears in Kelosa Blog we reserve the right to delete (in case of using swear words, insults or disrespect of any kind) and editing (to make it more readable) or undermines the integrity of the site