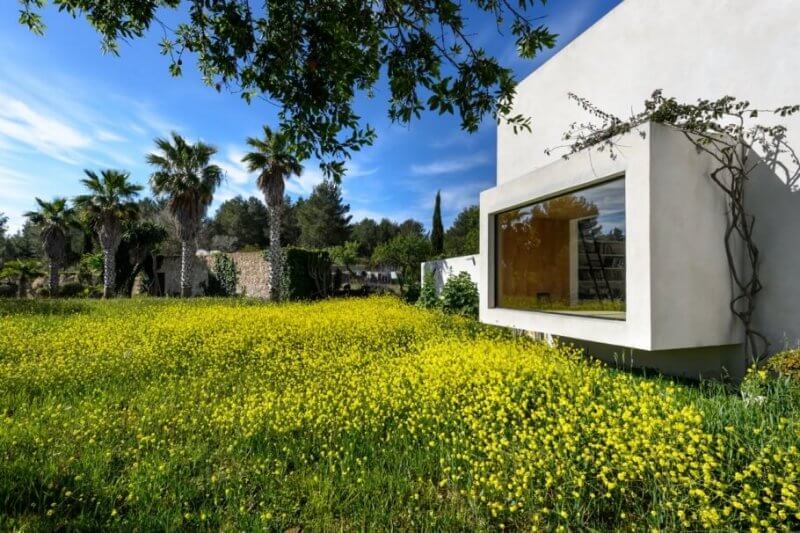

In the last two decades in Ibiza there has been a gradual trend towards the design of gardens with native and Mediterranean plants. This trend that has been accompanied in parallel through popularity of modern interpretations of the original architecture of the Ibiza, as seen for example in the popular Blakstad style. Many of Ibiza’s native trees are of symbolic importance, as well as for decorative purposes. As with vernacular architecture, when it comes to construction, indigenous gardens also have features that become important advantages:

Adaptation to the environment: less need for irrigation, intensive care, fertilizers or chemical products and the hability to recover from eventual setbacks and pests. Mediterranean plants tolerate drought well and even tolerate some degree of carelessness.

Resource and energy savings: such as the cost of water, electricity and other operating resources, as well as the costs of gardening and maintenance services.

Sustainability: the less need of fresh water, an increasingly scarce resource on the island, and the impact of invasive species are avoided. In addition, the biodiversity of native flora and fauna is promoted, supporting natural habitats, soil health and the longevity of local species.

Resilience: the Mediterranean climate can sometimes be abrupt and rough; Torrential precipitations can occur in the rainy season, prolonged droughts in spring or summer, causing an increase in the degree of salinity of the network water. These are points to take into account as they can particularly harm species less adapted to the environment.

Reproduction: native plants reproduce more easily in a native environments, so in mature Mediterranean gardens it is common for new specimens of existing plants to appear more frequently.

Continued flowering: as the climate is very sunny, it makes it possible to have a garden designed to be in bloom in all seasons of the year, with some plants (such as Bougainvillea) in bloom for almost 10 months.

Wide variety: the island climate of Ibiza, although considered semi-arid, is relatively mild and offers a greater variety of planting, with multiple possibilities of color, texture and shape. The different combinations that it offers adapt to a multitude of designs.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

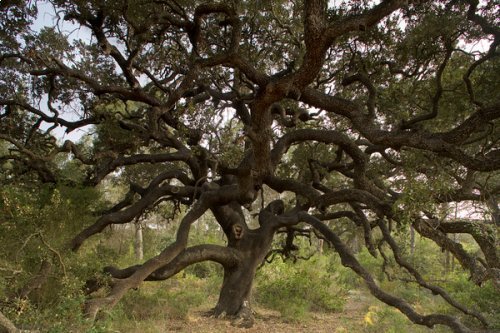

For about two decades, a multitude of owners of different nationalities have experienced a change of taste in the type of gardens that surround their houses. The tropical gardens full of palm trees, seas of tropical flowers and large lawns, so popular in the 80s and 90s, are giving way to simplicity of the origins and a more permacultural approach – that is, based on the principle of “working with nature, not against it”.

One characteristic example of this trend is the increase in wild gardens. This consists of leaving part of the garden totally or partially feral, that is, without any kind of care or intervention other than an initial plowing or, on rare occasions, an intervention by plague or disease. The result is what the Ibizan countryside offers by default, where everything is growing in disorder, a great variety of flowers of all colors, types and shapes.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

To add some more splendor to the wild garden, there are a variety of beautiful meadow flower seeds that can be scattered around the plots. These species can coexist in small spaces and each one will appear in its respective season. However, in this case the care technique is more sophisticated and consists in carefully removing the weeds between the plants so that everything develops, flourishes and comes out again the following year. This process requires some experience in gardening and above all to be diligent. For the rest, the seeds are well adapted to the weather and the soil of the island, therefore they do not require special care or fertilizers and they reproduce without much effort.

Ultimately, the Mediterranean garden recreates a relaxing sensation, through its soft-colored plants and flowers with distinctive aromas. For example, with the presence of lavender, rosemary and rockrose, a lush, aromatic garden is achieved with minimal care. A good method is to combine plants that bloom at different times of the year. Other plants, such as bougainvilleas or hibiscus, bloom practically all year round. Olive and lemon trees, while being among the trees best adapted to Ibiza’s climate, give an elegant character to the garden and a large quantity of fruits. To create a secluded environment, there are a variety of climbing plants, such as vines, on rustic-looking vertical trellises, making the most of the available space (especially for smaller gardens).

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

There are two types of gardens in Ibiza that fall into a special category and need a somewhat different approach. The gardens by the sea and the gardens with saline water.

Gardens by the sea.

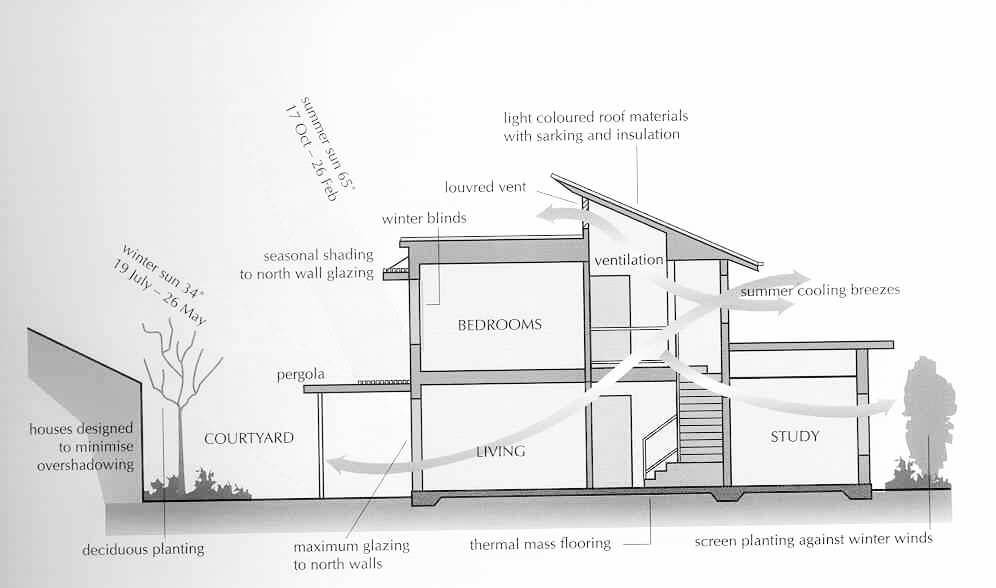

On a relatively small island, with an area of 572km², the influence of the sea extends far inland. There are, for example, strong storms that hit the island in winter, leaving trees bent in the opposite direction to the wind as witnesses of its intensity. It is important to know that these storms do not stop at the garden limits, therefore they must be taken into account to be prepared for the adversities that these gardens usually suffer.

The strong wind off the Ibizan coast can knock down the youngest plants, cutting off tree branches and shrubs. However, the wind is not the biggest problem, but the resulting saltpetre that is deposited through the wind on the earth’s mantle and, dissolved by rain or irrigation water, can damage the fine roots of many plants. These fine roots are the ones that absorb and transport water, so few plants can recover from this saline saturation. In addition, these salts carried by the wind also settle on the leaves and can burn them.

The most important step would be to choose plants that are salt tolerant, which also avoids excessive maintenance costs. These plants tend to be native to coastal habitats and other environments with high salinity, such as the salt marshes. An optimal garden near the sea should also contain mostly dense plants and shrubs, forming a firm structure of robust and wind resistant plants. Generally, this type of vegetation is low in height and has few flowers. The flowers should be select, more like touches of color than for the usual prominence that they usually have in gardens.

Palm trees, pines and cypresses, with their flexible and resistant trunks, are suitable for windy coastal locations. Deciduous trees have less surface area that the winds can attack, since they lose their leaves from autumn when the harsh season begins. Succulent plants have water reserves and are ideal candidates for low maintenance gardens and have a greater tolerance to sea winds. Last but not least, almost any kind of cactus are ideal in this environment, since Ibiza is considered semi-arid and in these conditions they resist practically everything.

© Kelosa | Ibiza Selected Properties

Summer is the most benign season for seaside gardens. Starting in autumn, the plants are put to the test and at the latest during the first winter of its life its put to the test whether a plant can resist the brackish winds. Strong winter winds in Ibiza blow 90% from the northwest, therefore the gardens on the south and southeast coast are largely more protected. In those areas one has more of an option of planting a variety of more sensitive species.

Gardens with saline water.

The residences in the south and southwest parts of Ibiza have a supply water that is of a higher salinity, especially in summer when more people use the water from the network. At some points in the summer you may have to buy bottled water to cook or make a simple coffee, but using that drinking water for the garden would mean an excessive cost.

Many kinds of plants suffer from the salinity of the irrigation water, for the same reasons that we discussed above, but in this case it affects in particular during the summer months. Saline irrigation water, added to brackish winds, can wreak even more havoc on plants that are not acclimated to these conditions. What usually happens in these cases is that the plants look good during winter and spring, due to the rainwater that dilutes the salinity, but when summer arrives they begin to lose their leaves and flowers, presenting an increasingly sickly state until there is no turning back, since its roots can’t tolerate the salinity of the soil, the plant dies.

“Mediterranean Garden” by HeatherW is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

To avoid dramatic scenarios such as the mass death of plants or an exorbitant water bill, there are two possible solutions: one is the construction of a water collection cistern for the rainy season (autumn and spring), which would involve construction, licensing processes and it is not entirely clear to what extent it would solve the problem; the more reasonable second option is to adapt to the circumstances and place plants that withstand both salinity and drought. In this case, it is recommended to plant them between October and April, when the abundance of rains and the more temperate climate help the young plants to adapt to their new habitat, gradually getting used to the increasing salinity, the strong sun and the summer droughts. Here is a quick list of saline water resistant plants.

Some steps that can be taken to reverse high salinity:

- Plow the soil, providing organic matter and sand, to increase the permeability of the soil.

- Install drainage pipes to evacuate excess water laden with salts.

- Abundant irrigation of fresh water that floods and wash the soil.

- Choose mainly resistant plants, in particular to the salinity.

- Do not abuse fertilizers, as they salinize the soil.

In the long run, the sea has the strength to beat the greatest precautions and care provided in a garden, so lowering the claims makes sense to avoid displeasure, considering the beauty of the seaviews in itself.

References:

About Index. Noahs Garden – Soulgarden for Earthlovers. Ibiza. [consultado 18 de agosto 2020]

Elías Bonells, José. Jardines junto al mar de influencia marítima (2017). Blog: Jardines sin fronteras. [consultado 20 de agosto 2020]